Fifteen years ago, over a long Tết weekend, Thuan Le Elston and her husband flew from Northern Virginia with their kids to Phoenix for her maternal grandmother’s funeral. After seeing her half Vietnamese children experience for the first time being around her huge extended family, Elston decided it was time to write a historical novel she had been planning, inspired by the stories of her grandmothers and her husband’s grandmothers.

A dozen years later, Rendezvous at the Altar: From Vietnam to Virginia was published. The novel traces the lives of four women: Anne’s upbringing in Virginia to her Mad Men-like married life outside Manhattan; Kim’s family as they survive French colonialism and the Vietnam War; Mary’s transformations through the Great Depression in the Midwest and two marriages; and Ty’s migration from Hanoi businesswoman to Arizona matriarch. Through a mother’s journal to her children and the four grandmothers’ narrations, Elston compares gender roles, parenting, aging, and dying in a multicultural family.

Elston, an opinion editor for USA Today, recently sat down for an intimate interview with her daughter Thai-Binh Elston, a research associate at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, about Rendezvous, her inspiration, and writing process.

~

Thai-Binh Elston: A core memory of my childhood is you working all day for USA Today, coming home, getting us ready for bed, and then heading back to your laptop to work on this book all night. What about writing this book made all those sleepless nights worth it?

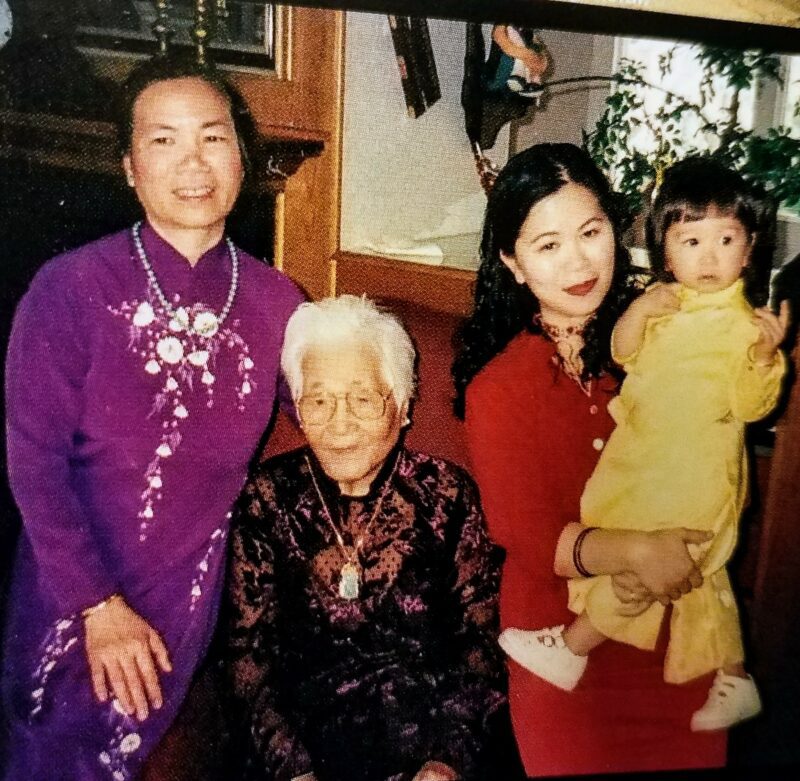

Thuan Le Elston: Bà ngoại was the last of my and your dad’s grandparents to pass away. You and your three brothers were still young in 2009, just ages two to 11. But I thought, this is it – one generation has gone silent and my kids are never going to know all the stories of their ancestors if I don’t put it down. That’s what drove me.

It took more than a decade of writing, researching, rewriting and rewriting, but now it’s all there in black and white. I wrote it for you guys, but all the work also taught me a lot. As I wrote in the book, what strikes me about these four women is that the two Vietnamese shared a culture but lived very differently, and that the two Americans might as well have come from different planets.

Thai-Binh Elston: Why write a book about my great-grandmothers rather than my great-grandfathers?

Thuan Le Elston: My ông ngoại died when my mom was 22, so I never knew her father. My ông nội died when I was not even five. I have a memory of my dad’s father on his deathbed and smiling as I fed him steamed peanuts. That’s it. But I remember growing up in Saigon with Bà ngoại and Bà nội. I remember listening to their stories, how they talked, how they moved. In Phoenix, I watched how Bà ngoại’s relationships with her 15 children and multitudes of grandkids and great-grandkids change as she aged. We took you kids back to Saigon to visit my bà nội before she died. They were both so dominant and so important to me for so long, but I only knew my grandfathers through stories. Through your female ancestors, though, you still learn about the men in their lives. I gave our male ancestors their own voice, too.

Thai-Binh Elston: This book contains a lot of dialogue on behalf of people you last spoke to decades ago or never spoke to at all. How did you put yourself in their shoes and find their voices?

Thuan Le Elston: It was tricky. That’s why it’s a novel, because of the recreated conversations. But I felt it was necessary to convey the whole arc of each person, the context of how public history affected their personal histories. Your dad’s maternal grandparents I never met, but I knew his paternal grandparents and watched them interact with you kids years before they died. So, I remember their speech, their cadences. I interviewed my parents-in-law about their parents for the backstories, and they were so generous and honest about both the good and the bad. What was even trickier was remembering my grandmothers’ speech and cadences and translating their Vietnamese into English. My writing desk was surrounded by multiple Vietnamese-English dictionaries and Vietnamese books of old sayings. Luckily, we also have old letters and photographs from both sides of the family to help me with anecdotes. Fitting together all the puzzle pieces, I hope I’ve recreated their past lives for not only you kids but also for future generations.

Thai-Binh Elston: What does your mother (my grandmother) think about your book?

Thuan Le Elston: She’s very proud. And as a child, I never thought I’d be able to make my mom proud. I was a dreamer and not a good student. She was always tough on me and blamed my dad for being too soft on me, because I was more like him. He was a poet and a musician; he was fluent in English, French, and Mandarin. He was an editor of an English-language weekly when Saigon fell in 1975 and we fled to America. But after he died in 1991 and I was a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, she and I have had a totally different relationship. We both realized I was more like her. She retired early in 1998 and moved from Phoenix to Northern Virginia to live with us once I started having kids. She helped raise all four of you guys. This book is also a tribute to my mom, your bà ngoại. As I wrote the novel and had questions, I’d call her for answers and she’d remind me of stories I had forgotten. I’ve learned so much from her. She has taught me how to live, and now that she’s 84, she’s also teaching us how to gradually say goodbye. She’s very Zen about life and death.

Thai-Binh Elston: I never met your dad (my grandfather), but I’ve always wished I had the opportunity to. What do you think he would say about your book if he were around to read it?

Thuan Le Elston: I’m so grateful for all the stories he told me over the years before he died the weekend I turned 25. As the oldest of five and the one who knew the most Vietnamese, I always took advantage of being the fly on the wall when adults were talking. But because I shared his love for literature and history, I learned a lot about his childhood, his parents and his favorite grandfather. I think he’d be amazed I actually not only wrote a novel but also got it published, no matter that it took a dozen years. I prayed to him quite a bit at our ancestral altar in the living room while I was writing this novel. I’m pretty sure he’s proud at how much he guided me from beginning to end.

Thai-Binh Elston works as a Research Associate at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and earned her BA in Public Policy at the College of William & Mary. She grew up in Virginia with her grandparents, parents, and three brothers, and currently resides in Boston, Massachusetts.

Thai-Binh Elston works as a Research Associate at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and earned her BA in Public Policy at the College of William & Mary. She grew up in Virginia with her grandparents, parents, and three brothers, and currently resides in Boston, Massachusetts.

Thuan Le Elston, a USA TODAY Opinion editor, is the author of Rendezvous at the Altar: From Vietnam to Virginia.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!