One of the clearest signs of the distance between Vietnamese in the diaspora and those in Vietnam is whether or not they recognize the significance of the name “Kiều.” Many in the diaspora, especially those who immigrated when they were very young neither recognize the name nor understand its cultural significance.

I posed the question “Who is Kiều?” to a handful of Vietnamese American women. I received an assortment of answers from “…some dude in a rice hat…” (I don’t think she was being funny), “you mean Việt Kiều?”, “don’t know” to “something not to name your daughter.” The last woman clarified: “She had a terrible life. Don’t name your daughter Kiều or after flowers.”

Alternatively, tune into the thoughts of Vietnamese writer and photographer, BeBe Khuê Jacobs, who lived in Vietnam until she immigrated to New York as a teen:

“I was told that it was what it meant to be a Vietnamese woman and my destiny as a Vietnamese girl. Kiều was stories from my childhood. Was the linguistic bible for my family. They quoted it like the scriptures. They recited verses that rolled around in the mouth onto the tongue; the words were chewed like nectar from sweet rice. Kiều was what we were fed during the famine years; we were fed words, poetry and Truyện Kiều to satisfy our hunger for grains of knowledge in the basket of scarcities.”

People in Vietnam, especially women, recognize Truyện Kiều (The Tale of Kiều) not only as Vietnam’s “national epic” but the epitome of its cultural brilliance and its “revolutionary” spirit.

Women like Jacobs who were born and raised in Vietnam are immersed in Truyện Kiều and a language replete with references to Kiều. They play games like Bói Kiều where they pray to Giác Duyên, the kind Buddhist nun who rescued Kiều, before randomly pointing to a verse in the epic poem to select a line that is supposed to prophesize their future.

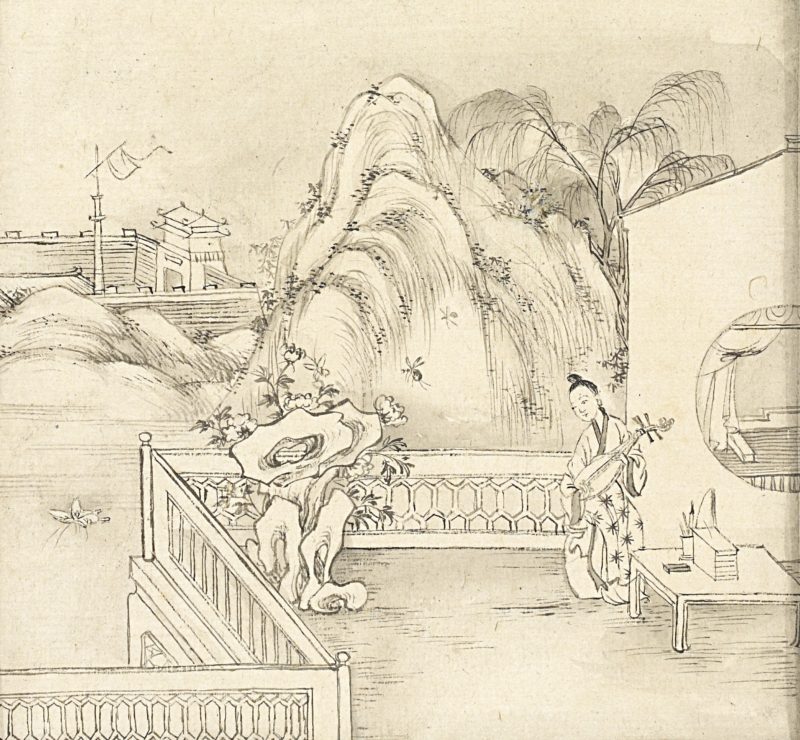

The main protagonist, Kiều, saw tragedy and betrayal three times but never lost her beauty and talent, nor her ability to trust. Kiều (a.k.a. Nguyễn Du, Vietnam, North Vietnam, South Vietnam, any Vietnamese woman who has been betrayed, any Vietnamese man who has been been politically sabotaged, anybody who has ever been fucked-over ever—thus, literally anyone) is an other-wordly beauty with immense literary and musical talent and unrivaled virtuosity. As a result of ingrained Confucian filial piety, Kiều refuses to consummate her love for Scholar-dude-lover-#1, Kim Trọng, only to regret this when she later sells herself as a concubine into a marriage to save her father from debt imprisonment. To her dismay, Kiều’s first husband pimps her into prostitution where she meets Client-dude-lover-#2, Thúc Sinh, who falls in love with her and buys her out of prostitution. This angers his wife who kidnaps Kiều and sells her into a life of servitude. Kiều runs away to a Buddhist temple where a nun, Giác Duyên, saves her and she’s momentarily safe until she is tricked into a second stint in prostitution. She meets Rebel-leader-dude-lover-#3, Từ Hải, who marries her and sweeps her away for a few peaceful years until he is betrayed and she is taken as a prize and married to a mandarin. Kiều does the honorable thing—throws herself into a river, only to have her suicide foiled by Giác Duyên. She becomes a nun for 15 years before reuniting with Scholar-dude-lover-#1 (who married Kiều’s younger sister at Kiều’s request) who makes her his legitimate first wife. Regardless, Kiều insists on celibacy, saying she’s unworthy of his love because she’s so sullied. They agree to live together platonically. Like they don’t have sex. Ever. Thus, Kiều ends her story regaining her virtuosity (but never getting her rocks off with Scholar-dude-lover-#1—denied to the end!).

Truyện Kiều, like no other Vietnamese literature, has a permanent fixture in Vietnamese culture as its most timeless heirloom. It has been and remains to be at the center of an emotional laboratory that shifts with the ebb and flow of political forces. Truyện Kiều is, in my opinion, about…well it’s about whatever people want it to be about—anti-feudalism, anti-Confucianism, anti-colonialism, anti-communism, and even anti-dissident-writerism—basically anyone or anything that is innately beautiful that has experienced subjugation and adversity and that exists at the mercy of forces out of their control—but that remains, despite it all, incorruptible, pure, and unbroken.

Truyện Kiều is actually an adaptation of a Chinese novel described as “mediocre” titled Jīn Yún Qiào (The Tale of Chin, Yuen, and Qiao) written by Qingxin Cairen, a pen name, no doubt, due to its scandalous anti-Confucian storyline. Nguyễn Du stayed faithful to the original story and infused it with complex Vietnamese cultural and historical sentimentalities to make it more relatable to Vietnamese readers. In Nguyễn Du’s hands, Jīn Yún Qiào, went from a forgotten soap operatic novel of the “scholar-beauty” trope to a national treasure. Despite its Chinese origin, Truyện Kiều is quintessentially Vietnamese because it is the most successful effort by Vietnamese literati to create a body of work with Chữ Nôm that would serve to preserve an intimate literary portrait particular to Vietnamese culture. And this it does so exquisitely.

Throughout the poem are reflections of Vietnam, its culture and its coastal identity. Take these few lines from Huỳnh Sanh Thông’s careful culturally-specific translation:

Thương tình con trẻ thơ ngây,

Gặp cơn vạ gió tai bay bất kỳ!

Đau lòng tử biệt sinh ly,

Thân còn chẳng tiếc, tiếc gì đến duyên!

Hạt mưa sá nghĩ phận hèn,

Liều đem tấc cỏ quyết đền ba xuân.

Pity the child, so young and so naïve –

Misfortune, like a storm swooped down on her.

To part from Kim meant sorrow, death in life –

would she still care for life, much less love?

A raindrop does not brood on its poor fate;

a leaf of grass repays three months of spring.

In this passage, Kiều is faced with sacrificing her true love in order to repay her father’s debt. The verse, “Hạt mưa sá nghĩ phận hèn,” which Huỳnh translates as “A raindrop does not brood on its poor fate,” is an allusion to a popular Vietnamese folk song which laments the fate of Vietnamese women of that era to the destiny of a drop of rain falling:

Thân em như hạt mưa rào (As a young girl, my destiny is like a drop of rain falling),

Hạt rơi xuống giếng hạt vào vườn hoa (It may fall into a well or onto a flower garden that is blooming).

Such references touched the heart of Vietnamese people who felt the raw melancholic beauty of the tragedy of their culture. In verse after verse, Truyện Kiều captured in vivid imagery and hypnotic language the life-story of a protagonist that everybody from the peasants in the fields to the literati with their books could love, in all of her tragic torment. To quote scholar Phạm Quốc Lộc:

“For a country perpetually fragmented by successive colonial systems and civil wars …Kiều emerged as a symbolic order that united the nation where it was torn apart by cultural and political antagonisms. Culturally, Kiều bridged the gap between the literati and his illiterate neighbors as both read and cited Kiều in their daily life. From urban spaces to rural areas, learned scholars and literary men enjoyed Kiều as an inspiring masterpiece of artistic creation, whereas common people recited it as a popular song. Verses from the tale even became part of the people’s daily expression.”

In researching Truyện Kiều, I fell into a chicken and egg dilemma. That is, Vietnamese literary critics and historians love to tie Truyện Kiều up with a bow of anti-feudalism and an air of dissidence that lends the poem to the national narrative of heroic victimization and revolutionary, anti-colonial zeal. Truyện Kiều is often lauded as a metaphor of Nguyễn Du’s anti-feudal, anti-Southerner, and anti-Nguyễn dynasty dissidence. Most accounts in English report Nguyễn Du’s alleged reluctance to serve under the dynasty that is often attributed to South Vietnam—the Nguyễn dynasty. They claim that as a former servant of the Lê dynasty, Nguyễn Du was forced to serve the Nguyễns, comparing Kiều’s forced prostitution to Nguyễn Du’s service despite his continuing allegiance to the defunct Northerner Lê Dynasty.

One can see the allure of this scenario to Communist Vietnam which often traces the origins of their victory in 1975 to the Tây Sơn rebellion. Thus, any ill will Nguyễn Du may have felt against the Nguyễn dynasty would be apropo to complete their anti-colonial “revolutionary” narrative.

A closer study of Vietnamese historical accounts narrates a tumultuous series of events which are strangely kept out of oversimplified internet historicals. These accounts, mostly in Vietnamese, place Nguyễn Du in the middle of the maelstrom of the Tây Sơn rebellion, a peasant uprising that tore through the Southern regions before spreading North with peasants pillaging and raiding region after region until a number of Nguyễn Du’s friends, families and colleagues were murdered including his older brother. If this conveniently omitted historical fact is true, can we just pause for a moment to imagine what this must have been like for Nguyễn Du? With this in mind, reconsider the metaphors of his popular epic.

After seeing terror rip through his community, Nguyễn Du joined his brother-in-law and others to attempt a failed plot to restore the Lê Dynasty. He then collaborated with others to return the single surviving member of the Nguyễn lords, Nguyễn Ánh, to Vietnam. So, if that is true, he actually wanted the Nguyễns to return to Vietnam. For his part, he was arrested by Tây Sơn officials and jailed for three months. Because he was famed for his intellectual and poetic talents, he was purportedly offered a position in the Tây Sơn dynasty. He refused and returned to the countryside. Two decades later, in 1802, Nguyễn Anh returned with the help of the French to seize back control of the country from the short-lived Tây Sơn dynasty. He then unified Vietnam and established the Nguyễn dynasty. Nguyễn Du was then invited to join the Nguyễn court, a post he is reported to have accepted reluctantly, still pining for the Lê Dynasty.

It is interesting to note, when reviewing history, what is left out and by whom. Little is said about Nguyễn Du’s animosity for the Tây Sơn dynasty while a great deal of emphasis is placed unduly on his alleged discomfort under the Nguyễn dynasty, despite the fact that he served faithfully until he died, receiving ample promotions throughout his life. Historian Keith Taylor points to the lack of evidence of Nguyễn Du’s alleged dissatisfaction. Moreover, these claims are ironic when considering what happened to former South Vietnamese civil servants, government officials, writers, journalists, artists, and veterans of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) under Communist Vietnam. Most were sent to re-education camps where they wallowed in hard labor (some until they died) the camps effectively silencing any who held any hope for a democratic South Vietnam. Their fate was remarkably different from Nguyễn Du’s exalted position in the Nguyễn court.

Really enjoy reading your essay!