I first encountered Monique Truong’s work through her first novel, The Book of Salt. I was just discovering Vietnamese American literature and was picking up everything I could find with a Vietnamese American author. Through their work, I was able to see bodies like mine, stories that were like my own family’s.

But Truong’s The Book of Salt was different. For one, it was a historic novel set before the Vietnam War and followed Gertrude Stein’s Vietnamese chef, Bình. It opened my eyes to the fact that Vietnam was not just a place of my parents’ time—but a place with history and a place full of stories and possibilities. And there was something else: its protagonist was gay. I was just beginning to understand my own sexuality and, reading Bình’s story, I saw a more accurate portrayal of my own experience: not something like my body but my actual body and, despite the different eras we lived in, his story was familiar to me.

To say nothing of the beautiful language of the book, written in stream-of-conscious style with the same love for words that Gertrude Stein would have had (though I hadn’t read Stein at that point yet).

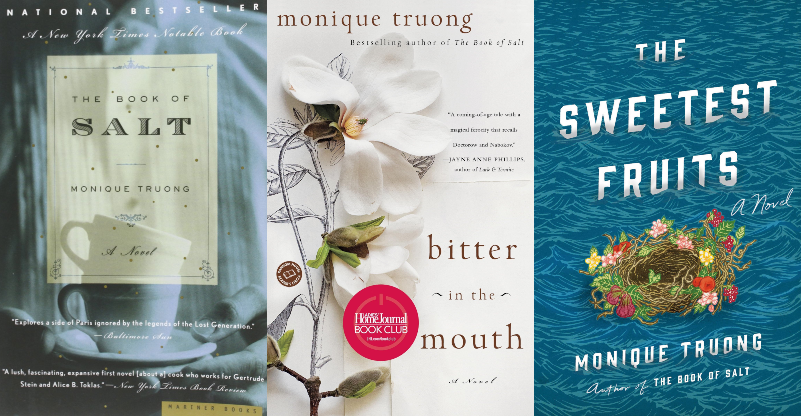

Since her debut, Truong rarely sticks to similar stories: each novel is a world apart. Bitter in the Mouth, took us to the American South and her latest, The Sweetest Fruits, is an epic spanning three continents in the late 19th– and early 20th– centuries. (Read more about The Sweetest Fruit in this review.)

Today, as I work on my own fiction, when I picture the type of writer I want to be, I think of Truong: to be a writer who continually surprises. At the same time, her work is a testament to the power of storytelling, especially for people who are told they are powerless. Through her work, Truong shows us that storytelling is power, words are power, and perhaps fiction is one of the most powerful things we have: you can tell so much, you leave things out, you can make things up. As Bình says in The Book of Salt: “My story, Madame, is mine. I alone am qualified to tell it, to embellish, or to withhold.”

Needless to say, I was thrilled to be able to talk to Monique via email about her work.

ERIC NGUYEN: How did you come to write a novel about Lafcadio Hearn?

MONIQUE TRUONG: For me, novel ideas are like the weeds that grow in the cracks of a city sidewalk. Inhospitable and unlikely environs (my inundated, scattered brain) and yet they (the ideas) insist, persist, and take over.

I came across Lafcadio Hearn’s name in a Southern Foodways Encyclopedia (everyone owns one, yes?), and the short biographical entry about him made very little sense to me: that Hearn (1850-1904) was born on a Greek island, came to the U.S. as a young man, lived in Cincinnati and New Orleans, where he wrote the first Creole cookbook published in the States, and then headed to Japan where he became known as an expert on Japanese folklore and fairy tales, passing away in Tokyo. That’s a lot of geography for one man.

I was intrigued enough to find a copy of his Creole cookbook, and that’s where I began with his oeuvres of over twenty some books. I quickly understood that Hearn was a man of his era: sexist. He wrote in his cookbook, La Cuisine Creole, published in 1885, that men were better cooks because they were more scientifically minded. What his commentary ignores, of course, is that in the U.S., women during that era were not admitted into the laboratory, except in rare instances. To decry a woman’s lack of scientific knowledge, given such prohibitions and lack of access, was silly and insulting. I’ve said elsewhere and I’ll repeat it here because it’s true: after reading Hearn’s cookbook, I didn’t want to cook from it; I wanted to get into a fight with the author. You can’t win a fight with someone until and unless you know them well. Their weaknesses, their strengths, and their tenderest spots.

The Sweetest Fruits is told from the point of view of four women—Rosa Antonia Cassimati (Hearn’s mother); Alethea Foley (his first wife); Koizumi Setsu (his second wife); and Elizabeth Bisland (his biographer). Why did you choose to tell the story of Hearn through these point of views, as opposed to a story through his own eyes?

Hearn’s point of view is well represented by his own published writing (over twenty-some books, including volumes of collected essays) as well as his personal correspondence. I wanted to hear from the other people in the room. In the biographies of Hearn that I read, it became clear to me that Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu were treated poorly by History. They were dismissed as illiterate, emotionally unstable, subservient, and/or economically desperate or dependent. I began to research their lives, and the more that I learned about them the more that I understood why Hearn was attracted to Alethea and Setsu, as both were storytellers in their own right. As for his mother Rosa, Hearn had turned her into the embodiment of “Oriental” goodness—Oriental is a flexible word, isn’t it?—while his Irish father was positioned as the less admirable “Occidental.” Hearn saw himself as a combination of both.

I wanted to invite Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu to the table, as it were. As for Elizabeth, Hearn’s longtime friend and first biographer (I also believe her to be his truest love), I invited her as well, including excerpts from the biography to represent the official History of Hearn. Her biography of him shaped his literary legacy and boosted his reputation as a Great Man of Letters. Her biography also repeated apocryphal stories about Rosa (most likely told by Hearn himself), deleted Alethea entirely from his life, and proffered stories about how Setsu and Hearn met that preserved his dignity (and Setsu’s, though she was not Elizabeth’s primary concern).

How do you think Hearn would have reacted to The Sweetest Fruits?

I think he would find The Sweetest Fruits compelling because the storytelling is from the points of view of the women in his life.

Rosa’s story about how she met Hearn’s father to-be would shock the author because it is counter to the story that he has told about his parents and that biographers have repeated. The most commonly repeated narrative of their meeting is that Charles Hearn spotted Rosa Cassimati walking on the streets of her island town and struck up a conversation, which then led to a love affair. Based on the research that I’ve read about unmarried women of Rosa’s class, they were not allowed to walk unaccompanied and were often sequestered within their home until marriage. It was, therefore, highly implausible that this was how the meeting occurred. On the pages of The Sweetest Fruits, I offer a different version that takes into account Rosa’s gender and class-dictated day-to-day existence, context, and circumstances.

As for Alethea and Setsu, Hearn would recognize them, but as Setsu says in The Sweetest Fruits, “Their facts you will recognize but, perhaps, not their stings.” Both these women of color could not afford to see the world that they shared with Hearn through the rose-colored glasses that he did. They saw what he ignored or chose to ignore.

Most of all, I think Hearn would gain a greater respect for Rosa, Alethea, and Setsu because he would recognize that they too had crossed boundaries, flaunted societal convention, and created for themselves a life as epic as his own. I do believe this, because if I had thought otherwise—that Hearn did not have the capacity to empathize and see his world differently, when the stories were relayed to him—I would have never stayed with him for the eight years that it took to research and write this novel.

The book is very much about migration and the privilege of free migration—who gets to migrate, who has to stay. While these characters are very different from me, their stories, told in this way, got me thinking about the Vietnamese diaspora. I think of my parents who were able to leave Vietnam in 1975, but I also think of the family members and others who had to stay behind. Has your experience as a former refugee, as a Vietnamese American, as a woman informed your understanding of these characters? If so, how?

As a refugee who came to the U.S. as a six year-old child in 1975, I’m drawn to stories of people who choose to displace themselves, to live in exile from their country, culture, and language(s). When I say “drawn to,” what I really mean is that I cannot understand why they would do such a thing. Because such an existence is fraught with difficulties and psychological trauma. I’ve observed our Vietnamese American community—those of my parents’ generation in particular—and I’ve seen a lot of unaddressed, unacknowledged, and unresolved psychological pain. We may choose to call it “nostalgia,” but what it is, in fact, is trauma and a fractured sense of self. Yes, some within our refugee community have prospered economically but at what cost? Also, at what cost to their children and their children? What does it mean to “make it” in this country if you then turn around and vote in a government that closes the door to refugees, immigrants, and migrants. That, forgive me for being blunt, indicates an internal rot, a state of mind that hates itself.

Speaking to your body of work, food has played an important role in all your books. In The Book of Salt, the main character Bình is a chef. In Bitter In the Mouth, Linda has synaesthesia which allows her to taste words. And in The Sweetest Fruits, food is evocative of place as well as a cornerstone of relationships. Why is food such important theme in your work? Put another way, why is food worth exploring?

Here’s one of my favorite quotations from M.F.K. Fisher, the great American food writer and essayist: “People ask me: Why do you write about food, and eating and drinking? Why don’t you write about the struggle for power and security, and about love, the way others do?” The answer is, of course, found within the question as posed. When Fisher writes about food, eating, and drinking, she is writing about power, security, and love. I would humbly say the same about myself.

I see the world through a specific set of lenses, and food and cooking are two of them. I don’t use these lenses to make my writing more palatable to readers. I do so to remind myself of how undervalued, unappreciated, dishonored those who are the growers, harvesters, cooks, and “servers” tend to be. The daily meal is a blessing, and yet those who make it possible are often treated as if they are a plague, often because of their gender, their legal status, their skin color, or their “race.”

Both of your historical novels (The Book of Salt and now The Sweetest Fruits) focus their attention on the so-called minor characters in the lives of famous people. Why do these figures interest you and what do you think we can learn from them?

The “minor” characters interest me because they were, in fact, present within history and were witnesses and participants, and yet few historians have bothered to inquire into what these folks saw, felt, and understood about the world. It takes a heck more research and labor to locate the history of these so-called “minor” characters. The historians who engage in these inquiries deserve bonus pay as well as our utmost respect. As Professor Saidiya Hartman noted in her 2008 essay “Venus in Two Acts,” the archive is empty when it comes to the history of the enslaved and the subaltern, and it takes “an act of chance or disaster” to produce “a divergence or an aberration from the expected and usual course of invisibility,” which then brings these persons “from the underground to the surface of discourse.”

In short, the “minor” characters offer us a fuller understanding of the past.

You’ve shared on multiple occasions about seeing Barbara Tran reading poetry at the Asian American Writers Workshop in the 1990s and how that affected you, seeing a Vietnamese American writer at a time when there were so few. Today, Vietnamese American writing is thriving. We are publishing poetry, fiction, memoirs, and drama. Some of us have even won the Pulitzer! What do you think of this abundance of Vietnamese American writing and what do you hope to see in its future?

I’m grateful and heartened every day for the fact that there are more and more Vietnamese American literary voices, but I think we must also acknowledge that within the U.S. publishing and literary establishment there has been a system in place that has allowed for only one or two voices to emerge as the designated literary “star.” Just take a look at the New Yorker over the past few decades and count how many writers of fiction, who are people of color, are included within the pages. There usually has been one. It’s clear how the establishment thinks: “Dear White Readers, If you’re only going to read one—and we know you will read only one—then here’s the one.” I hope to see that change. I hope that Vietnamese American readers will celebrate our Pulitzer and National Book Prize winners while still being curious and open to the voices that are not being celebrated and acclaimed by the mainstream. I say this not to take anything away from the prize recipients (because I too have received a few), but rather to encourage us all to read widely and to determine for ourselves what moves us and brings us joy. In other words, let’s not allow the literary mainstream to dictate to us whose writings are of value and worth.

More info on The Sweetest Fruits here

Upcoming author events here: http://monique-truong.com/events/

Contributor Bios

Monique Truong was born in Saigon and currently lives in New York City. Her first novel, The Book of Salt, was a New York Times Notable Book. It won the New York Public Library Young Lions Fiction Award, the 2003 Bard Fiction Prize, the Stonewall Book Award-Barbara Gittings Literature Award, and the 7th Annual Asian American Literary Award, and was a finalist for the Lambda Literary Award and Britain’s Guardian First Book Award. She is the recipient of the PEN/Robert Bingham Fellowship, Princeton University’s Hodder Fellowship, and a 2010 Guggenheim Fellowship.

Eric Nguyen is the Book Reviews Editor for diaCRITICS.