Tran Le Khanh’s poetry amazes with what it achieves in the space of four lines. In this first English translation of Tran’s poetry The Beginning of Water (Sự Bắt Đầu Của Nước), Bruce Weigl and Tran have collaboratively translated selections from his previous poetry collections. While Tran is well-known for the lục bát or six-eight form which characterizes the ca dao or folk poetry tradition as well as classics such as Truyện Kiều, most of his poems here are quatrains which furthermore rarely ever reach six or eight syllables per line. In the introduction, Weigl observes that Tran’s poems are not nature poems, love poems, nor religious meditations. I would suggest that this is only because Tran consummately fuses this triad, as his poems bring the Buddhist devotional practice to bear upon the material world of nature and the inner world of passions.

While his poems dwell upon the nature of concepts such as samsara and the non-self, they do not seal themselves away from human endeavors such as love and desire. Tran laughs at “the silly way people try to diminish beauty / who can make a flower wither at once” (“the rain gets old”) because he perceives the eroticism which palpably inheres in the physical world: “the naked wall / the naked drop of water / embrace together / the same invisible dream” (“the current”). In another poem, Tran further explores this fluctuation between romantic love and Buddhist spirituality through the story of Chị Hằng and Chú Cuội, the Vietnamese variant upon the Chinese myth of the moon lady:

hằng

em hất trăng khỏi nước

cạn đêm

thuyền không trôi

ai đưa em về trời

sister

she scoops the moon out of water

drying the night

but the boat cannot move

who can bring her back to the sky

In his esoterically protean style, Tran relates the moon, water, night, and heaven to one another in order to convey Hặng’s desire to touch the moon through its reflection in the water, to row herself back to the sky on the currents of the night. This agile interplay of symbols, so subtly folded into the language of the original text, is sometimes obscured in Weigl’s translation.

One of the challenges of translating Tran’s poems is to reproduce its imagistic quality without imposing an external logic upon them. This is compounded by the challenge of translating Vietnamese, the syntax of which is less reliant upon grammatical connectors than in English. As such, Tran’s poems can present a loose succession of images in a way which an English translation cannot always keep up with. Consider, for instance:

nhiệt tình

hạ về

những chiếc lá nóng bức

con đường tốt bụng

cởi chiếc áo bóng râm

enthusiasm

summer

heats the leaves

so the road of kindness

removes its shade of trees

In this poem, Tran relishes summer by considering blazing leaves and a pleasant road, and it is only in the final line that Tran personifies the road as suddenly undressing itself of its shadows. In the English translation, these various images are melded into a single sentence with a causal logic.

The spareness of language which deeply enhances Tran’s imagism is, at times, also jilted for the sake of clarity:

mai

em

mở lòng từ bi

trăm năm hồ điệp

lơ la lối đi

mai flower

she

opens compassion in her heart

a hundred-year-old butterfly

jukes to the flower not minding its path

While the Vietnamese text is evocative of a lullaby, Weigl can only allude to this melodic quality through the word “juke” as a double entendre. Likewise, Tran’s poems are rife with internal rhymes which cannot always be reproduced such as these three powerful syllables “châm thêm đêm” which becomes deflated as “adds darkness” (“light”). The non-Vietnamese should further beware the intermittent typos such as “soul of frog” instead of “soul of fog” (“how to keep it”) or “to cleave his shadow at every dusk / 8,400 times” instead of “84,000 times” (“cleaving wood”), a number which significantly reappears in other poems.

To Weigl’s credit, however, the majority of the translations adhere very closely to the original lines. In several instances, Weigl complements Tran’s rhyme and rhythm schemes with his own adaptations, such as the alliteration in a particular line, “biển biết bí mật”, ominously transcribed as “the sea knows the secret” (“the sea’s salty pain”). At other times, the translation feels like an improvement upon the original, whether or not Tran partook in this process of revising through translation. In one poem, the muddled redundancy of poetic description acquires the intensity of a fable in Weigl’s pen:

đêm dài

vũ trụ lung linh giãn nở

đôi đồng tử nhỏ dần

con chó sói tru dài

rừng xưa khàn đặc trong cuống họng rỗng

rốt ráo không

long night

the universe is expanding glittering

the wolf’s pupils getting smaller

when the end has come

the wolf shouts a long howl

in its empty throat the ancient forest is hoarse

Tran’s dense and compact poems urge a re-reading even in the midst of the initial reading. In its immediacy, his poems feel akin to miniature paintings, wherein the process of visual scanning turns gradually inwards. His reflections upon the seasons and the natural elements also serve as reflections upon creation, death, rebirth, and the nature of time. Indeed, Bruce Weigl describes Tran’s work as partaking in Vietnamese poetry’s recent “metaphysical turn” which pursues that which “exist[s] beneath the surface of things.” Blurring the boundaries between human, fauna, and flora, Tran prods us towards a more basic recognition of what it means to exist in this world. In one of Weigl’s most sprightly translations, the speaker contemplates the sonic unity of the cosmos: “insects / swallow the sky into their bellies / for every midnight choir / an insane orchestra” (“oneness”). Borrowing from the tradition of Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Tran’s poems not only personify nocturnal insects but also narrate birds and leaves becoming human (“coming back”) and statues returning to life (“the everlasting dance”). Through the transformations which abound in The Beginning of Water, we are gradually guided backwards toward our origins, as revealed in the title poem: “memory / is a river / where a man follows a school of fish / swimming against the current.”

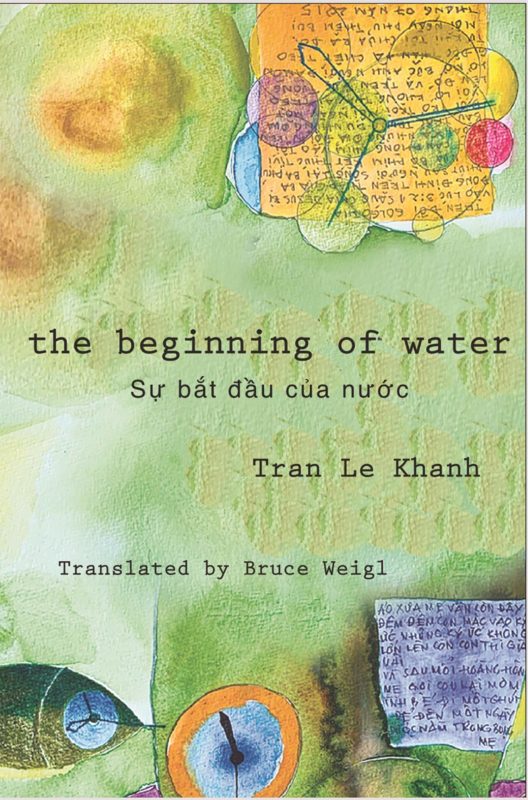

The Beginning of Water

by Tran Le Khanh

translated by Bruce Weigl

White Pine Press, $17.00

Contributor’s Bio

Sydney To is an English PhD candidate at UC Berkeley, with research interests in Asian American literature, transpacific Vietnamese literature, critical refugee studies, and biopolitics. His work has appeared in Asian American Literature: An Encyclopedia for Studies and Asian Review of Books. is an English PhD candidate at UC Berkeley, with research interests in Asian American literature, transpacific Vietnamese literature, critical refugee studies, and biopolitics. His work has appeared in Asian American Literature: An Encyclopedia for Studies and Asian Review of Books.

Thank you Sydney To for your generous and thoughtful critique of Tran’s collection of poems. I’m delighted that you found something of value you there, and happy to say that Tran and I are already one hundred short poems into a longer collection. We like to work together but Viet Nam is closed to international travel and I haven’t been able to get a visa. Anyway, thank you again for your astute consideration of our translation. Bruce Weigl

Thank you Bruce! I appreciate all the labor which went into this translation.