“There is no truth. Only a version. Aversion. A verge. A vengeance,” the acclaimed poet Paul Tran writes in their debut poetry collection, All the Flowers Kneeling. Poetry has served Tran by being all of these things. A queer Vietnamese American poet, a child of immigrants, and a survivor of sexual assault, Tran narrates historical, familial, and personal trauma in their poems.

All The Flowers Kneeling draws from the Western archive and landscape, where Tran wrings the “voice” of the marginalized body from the Master’s “violence.” Tran’s ekphrastic poems use Renaissance paintings to meditate on sexual and psychological violence. The speaker “I” remains in control across an array of personas, whether as one of the many cadavers that Andreas Vesalius publicly dissects to produce his human anatomy books in 1543—a cadaver who claims “knowledge was me” more than the spectators could ever know—or “the most beautiful bitch in the world” burning in the Santa Ana “devil winds” of Southern California while asking,

“Am I selfish

for wanting things

to make sense? To matter?

To amount,

in the end, to something

more than a tally

of days and nights?”

Tran brings care to all aspects of how their trauma and their mother’s trauma is told through poetry—from diction to sound to form. In a podcast with Poetry Foundation, Tran shares, “I don’t want anything I do to be an accident, because I don’t think anything that’s happened to me was an accident.” Tran handles the sexual violence that the speaker and their mother experience with the utmost care and tender language, conveying the collection’s themes of survival and love.

The poetry collection is divided into four untitled sections. A series of fourteen poems, “Scheherazade/Scheherazade,” is split between the first section and the last section. The first seven poems of “Scheherazade/Scheherazade” contain fragments of the college dorm room, where Tran was sexually assaulted, or the seaside, where Tran’s mother and other women were abused by soldiers during the Vietnam War. Tran is trapped in traumatic memory, but these poems prepare Tran to find “the way out” through their deliberate repetition and precision in the rest of the poems in the collection. In the last seven poems of “Scheherazade/Scheherazade,” Tran delivers power and revelations about “the long journey in silence” of surviving trauma.

As a Vietnamese poet, Tran inherently constructs and tenderly deconstructs how Vietnamese refugee families “recount and recant” the traumatic past. Like many other Vietnamese American authors, their writing navigates a Vietnamese American memory that is modified each time an experience is recalled; it is a mode of survival, when the lived reality is too violent and painful to bear. At times, the elders offer no altered memories at all, just silence. Tran’s mother tells multiple versions of her assault in the third section of “Scheherazade/Scheherazade,” but in one version “there’s no story” —the mother is silent, insisting “Nothing happened.” The younger Vietnamese American generation often becomes frustrated with the older generation’s refusal to speak about the past, wishing that they could find some way to access their Vietnamese heritage without re-traumatizing their elders.

But Tran is a rare narrator who meets their mother’s silence with an empathic silence around their own trauma. Tran interweaves their mother’s pain with their own narratives of pain in the first half of “Scheherazade/Scheherazade.” Instead of inquiring about their mother’s silence, Tran understands that they both withhold sharing their trauma because the Vietnamese “think of pain and blame / as objects requiring purpose and possession.” In another poem, Tran admits, “It’s easier, with the truth, with those I love, to be spare than unsparing.” Both Tran and their mother want to protect each other from blaming oneself and “appropriat[ing] the pain” out of love. But “[t]hat’s not love,” Tran realizes. Tran challenges Vietnamese readers to reconsider how they can communicate their love and pain in a way that is not self-sacrificing or self-loathing or transmitted solely through intergenerational trauma.

In addition to allusions to the Western canon, Tran brings Vietnamese letters into their poetry through Buddhist mythology. In section twelve of “Scheherazade/Scheherazade,” Tran paints a tranquil scene of their mother, sweeping in the temple courtyard, but juxtaposes it with the “leaves like shrapnel or ships crossing a darkening sea.” Tran’s mother sweeps up the pieces of her traumatic past and tells her son that “she was spared / because she had promised her life to serve / Ngài Quán Thế Âm.” Ngài Quán Thế Âm is the bodhisattva of compassion who listens to the cries and suffering of the world. In the single sentence that makes up section twelve, Tran learns from the way their mother survived and spared her future from the trauma she experienced. Tran writes,

“I got down on my knees

in front of the bodhisattva, my broom cast aside / … /

and I

wiped the earth from her feet with my own hands.”

Tran prostrates before Ngài Quán Thế Âm and offers themselves as their mother did, to press on and leave behind their trauma a little more every day.

In the section “Spring” in the poem “Year of the Monkey,” Tran alludes to Buddhist mythology as they explore the blurry expectations and responsibilities of being a Vietnamese American child of immigrants—to be both the self-sacrificing parent and the filial child, to be the one who can provide all the answers for the family, as well as the one who is taken care of. Tran writes about Ngài Mục Kiền Liên, one of the Buddha’s disciples who saves his mother in Hell by trading his soul so that she can be reincarnated into a better next life. Tran resists a possible straightforward analogy and instead they stand in as Ngài Mục Kiền Liên’s mother while their own mother becomes Ngài Mục Kiền Liên. Tran asks hauntingly:

“Am I him? Am I the mother? Am I waiting for my mother

…to save me, to trade her future for mine? My mother…

left me her past to survive. She left me behind

in Hell, where I had to find a way to save us both.”

Tran’s allusion tries to resolve the roles of mothers and sons when both are suffering in a traumatic, metaphorical hell. Leaning into the unstable family roles in an immigrant family, Tran considers themselves both as the child who rescues the mother and the mother who is rescued. Role reversals inevitably take place in the Vietnamese immigrant family when parents, with limited English, must rely on their American-educated children to navigate American structures and systems. The child becomes an adult, a parent to their parents in serious matters, official paperwork with government, school, and bills. The line “to trade her future for mine” also brings to mind the lessons of gratitude and filial piety that children of Vietnamese immigrants grow up with – that our parents have sacrificed a lot to give us a future, most importantly an education, in the United States; that is how our parents saved us, and why we must succeed moving forward.

Yet Tran experiments with this Vietnamese immigrant family condition, so generationally divided, and recasts the familiar self-sacrificing Vietnamese elder like their mother into Ngài Mục Kiền Liên, the son, a younger person with still a wide future ahead of him. Tran challenges the younger Vietnamese American reader to remember their parents’ own youth, and the future they traded as not a faraway sacrifice but a tangible experience, a rescue that we are experiencing and benefitting from.

Throughout the poems of All the Flowers Kneeling, Tran’s mother appears again and again, alongside Tran’s inquiry and attempts to rationalize or overcome their pain. Tran’s mother saves them through example as she serves Ngài Quán Thế Âm, delivers them to a better future as Ngài Mục Kiền Liên, and introduces them to the story of Scheherazade in the first place:

how my mother told it to me

when I was a child, how I had no idea

it was her gift to me, how to survive

we told the story of our survival.

The Vietnamese mother’s presence represents how Vietnamese American history and memory informs the way Tran processes their own traumatic past. More importantly, Tran’s debut collection testifies that the younger Vietnamese generation inherits more than war history and trauma. We receive survival tactics, lessons of pressing on and loving, from our Vietnamese elders and their journeys.

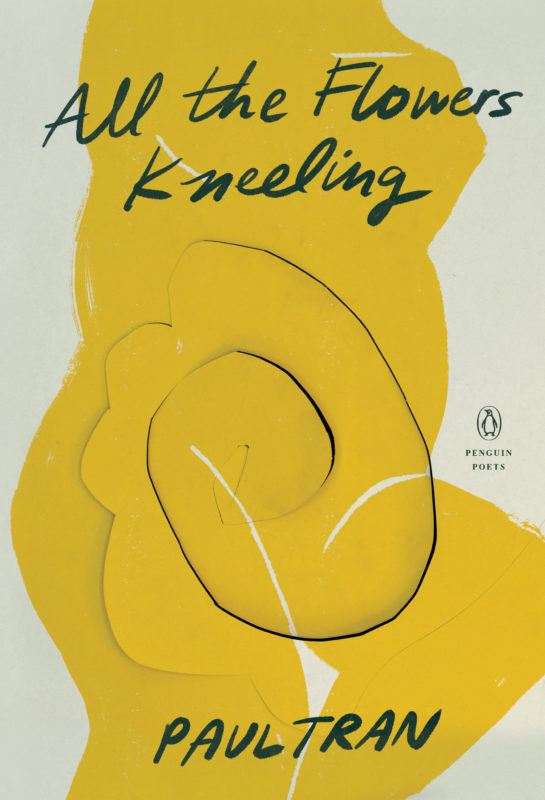

All the Flowers Kneeling

by Paul Tran

Penguin Books, $18.00

Contributor’s Bio

Cathy Duong is a current junior at Yale, majoring in English. She enjoys (over)analyzing all things Vietnamese, from the briefest references to Vietnam in Western pop culture, to art, literature, and film created by the talented Viet diaspora.

Cathy Duong is a current junior at Yale, majoring in English. She enjoys (over)analyzing all things Vietnamese, from the briefest references to Vietnam in Western pop culture, to art, literature, and film created by the talented Viet diaspora.