Jessica Q. Stark’s poetry collection, Savage Pageant, centers itself around Jungleland, an animal theme park and training facility founded in the 1920s. Exploring the concept of spectacles and who or what is deemed one, Stark’s poetry illustrates Jungleland characters like the MGM lion, actress Jayne Mansfield, whose passing aided the park’s notoriety, and tiger-trainer-slash-performer Mabel Stark. Savage Pageant drives its readers to evaluate not only the spectacle-ness of Jungleland, but how we interact with and reinforce contemporary spectacles like social media, pregnancy, space, and death.

BRI GONZALEZ: I want to start with a small anecdote. A couple weeks after the pandemic started, my friends and I were obsessed with this welding YouTuber who lived in Montana. We researched all these things to do as if we were going to go visit, and we came across this website listing the top ten must-see attractions. One of them was the grave marker of a circus elephant named Old Pitt. She was 102 and died by a lightning strike. You can still go visit her today. She was one of the first things I thought about after reading Savage Pageant. I want to know how you first stumbled upon Jungleland. How strenuous was the research? Was there anything you found that you weren’t expecting?

Jessica Q. Stark: I researched it for about a year before I wrote anything, any poems. I had peripherally heard about it when I was growing up, it was a part of Southern California folklore. But it was brief stuff, like somebody’s grandmother would say she remembers hearing lions roaring over Highway 101. It was spurious; people didn’t talk about it too much. I was always fascinated with Hollywood having grown up near there, but also out of step with it. I grew up in the suburbs, so I was about thirty minutes to three hours outside of L.A. proper, depending on traffic—a very inside/outside place in context to Hollywood. Jungleland seemed like an interesting receptacle for thinking about Hollywood gossip and regional folklore that has nothing and everything to do with how a culture reflects within that space.

The more I dove into it, it seemed like a fascinating place that few people have written about or paid much dedicated attention to. There’s one book out, but it’s part of a series of hokey historical registry sites. It’s like a coffee table book, y’know? Though it was important for finding some rare images. They compiled photographs and that comprised the book. Beyond this book, I don’t think much attention has been dedicated to Jungleland.

The research mostly took the process of looking into internet archives, some YouTube stuff, Internet forums, unofficial avenues. Looking into Jayne Mansfield’s connection in older newspapers, which was fascinating. I arrived at Jungleland because I was interested in thinking about spectacles and who gets made a spectacle and who gets to tell their stories. I wrote a chapbook before Savage Pageant called The Liminal Parade in 2014, and it focused on Britney Spears in juxtaposition with the Saint Louis World’s Fair, which is another form of intense spectacle in U.S. history. I haven’t ever been a big Britney Spears fan, and this was before the #FreeBritney conflict, but I was interested in how people love, admire, and destroy celebrities in the public eye. So that chapbook laid a certain foundation and explored themes that I’m still interested in.

BG: I love that Jungleland ties into both folklore and the idea of celebrities—they can kind of be the same thing with the way Internet rumors spread, creating false narratives that live on even past a celebrity’s height. And I love the way you approach those ideas in your work, especially with Jayne Mansfield. When and how did you first find out about her?

JQS: I think there was some information about her son’s attack by a lion at Jungleland, and the whole story around that mauling is so bizarre. There are all these rumors that Mansfield was a frequent visitor to Jungleland, but when the mauling happened, it was rumored that she had a love tryst with the leader of a Satanic church, Anton LaVey. There were staged photographs—you can find them online—of her with him in her ridiculous, kitsch mansion. The rumor is she made a deal with him—with this extension of the devil—to save her son when he was in critical condition as a result of the lion attack. They thought he was going to die, but he recovered. A few months after her so-called deal, her boyfriend died, tragically. And then she died in a gruesome way; there were rumors about her death and about her being decapitated by a passing truck on a highway in car crash. The details of which were later revealed to have been exaggerated. It was so absurd and sensationalist.

The thing about Savage Pageant is that it’s a haunted text. It has haunted me in weird ways, and it constantly plays with the very blurred lines between serendipity, chaos, and connection. For example, I had never met anyone named Mabel, but when I started writing Savage Pageant, I met three people named Mabel in that same year. That’s absurd! I moved to Florida two years ago, and the original owner of the house I live in, which was built in 1913—his last name was Savage. Things like that keep happening with this book, and it’s easy to say that I’m out of my mind, but it’s merely coincidental. In keeping with that, the Jayne Mansfield events are disparate connections made around a place that are in part chaotic and in part serendipitous, though no one can really pay attention to connections like these because doing so often goes against logic.

BG: I’ve also had those experiences—the way your text is haunting you. In a way, that’s almost a personal spectacle.

JQS: I think you’re so right. And that’s art! The creation of art involves being obsessed or obsessive—the word obsession has such a negative connotation in our culture, but that attention is crucial to producing art. Being obsessed with things when everything around you is telling you not to.

BG: If you had to spend one day in the body of an animal, which would you chose? What would you do for the day?

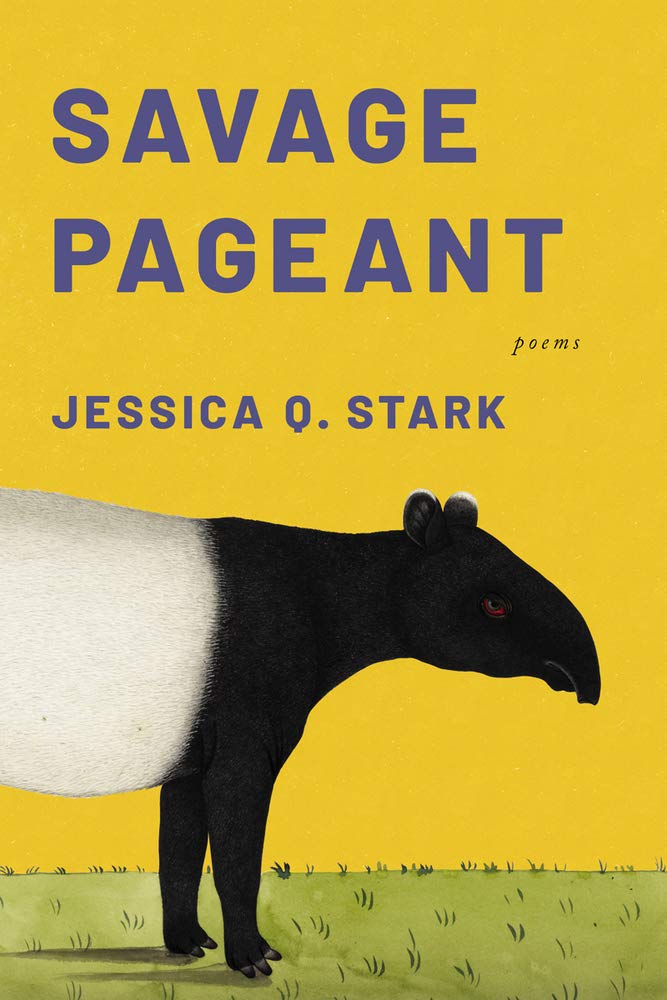

JQS: That’s a hard one. I have to say a tapir, like the one featured on the book’s cover. The story behind the tapir image is it’s derived from an anonymous painting, very old, and it was produced and included in a catalogue for recording an act of diplomacy between countries during the 17th century. These kinds of accounts were often produced and it’s interesting to think about this tapir and its reproduction through art as more a record of two nations’ relationships. It’s not known who drew it and it’s weirdly contemporary looking. And in some Asian cultures, the tapir is seen as the end result of combining all the leftover parts of different, more beautiful looking animals; whoever made the universe had mismatched, not-great parts of say—a lion or a tiger. The tapir is composed of those parts put together. Being a mixed-race person, I feel so much affinity with the tapir. It’s also such a striking image. This tapir looks like such an awkward beast—in some respects, it looks pregnant, which I felt was appropriate in that I wrote the majority of this book during my first pregnancy. It also has such a menacing glare back at its audience and its creator, which I feel is a defining feature of how I thought about crafting this book.

BG: In line with ghosts and hauntings, the Google Maps that you utilize almost express a ghost Jungleland—a mass grave of animals beneath strip malls and suburban neighborhoods. What pushed you to use those images? Attached to that, do spectacles ever stop being spectacles? Even after death, do they still have a spectacle-ness?

JQS: I really wanted to keep those Google Images in, though one an editor suggested I take them out. However, they were important to me because Savage Pageant is concerned with the ways we view certain places. The format of Google Maps is a very specific interface that organizes how we conceptualize a place, though it actually leaves out a lot of information, details, and history. The richness of this place is completely absent on a Google map. That was something I was drawn to and dedicated to keeping in. I felt that inviting a second look is so important for Savage Pageant. It’s thinking about how we shape space visually, how we represent space visually, and the limitations of our tools, our gaze.

Can something be a spectacle after death? Absolutely. Oftentimes, I think people use absurd forms of memorialization, to the point of death becoming a spectacle. I’m a huge admirer of the writer Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. She wrote one hybrid poetic text and then she was horrifically murdered. Her work is so rich, and it’s interesting that it plays against the concept of spectacle, the very details of her death—it’s a challenging text. Dictee is difficult, wide-ranging; it’s alive in a lot of ways. It’s one of those texts you read five times and every read you get something new. Even though it counters death as a spectacle, it’s also very exploratory of death.

A lot of people focus on the conditions of her death, however. More so than her work itself. That’s one way in the niche literary world that I feel death becomes a spectacle. But this, of course, also happens in celebrity culture. Especially on social media, people air their responses to a celebrity’s death. There are many forms of performance and death doesn’t save us from these weird and troubling modes of being and performing in front of one another. So no, I don’t think you can get away from being a spectacle, and death most often intensifies a certain type of spectacle. Jayne Mansfield’s death was in and of itself a spectacle.

I think it’s interesting and disturbing how people grapple with, deny, resist, perform around death. There’s a good book called Memorial Mania by Erica Doss. It looks at all the different ways we memorialize death, either in temporary ways or with permanent statues, etc. It’s fascinating.

BG: I’m from Mexican heritage, so that makes me think about ofrendas and Día de Muertos, how we sensationalize death in a cultural context.

JQS: Right, and yet we’re so scared it. A lot of that performance is hinging on real terror in white culture. My mother is Vietnamese, and for Vietnamese people, death is, in Buddhist culture at least, celebrated to some extent. We celebrate a loved one’s death day each year, for example. I feel like Vietnamese people love believing in ghosts—I believe in ghosts—which in my mind isn’t in the same way as in American culture, which is always related to sensational terror. Everyone is mostly terrified of death.

BG: Related to the social media point, I was wondering what your thoughts are on the current state of social media, especially TikTok and how it strengthens the relationship of spectacles and spectators.

JQS: I got TikTok when it first started getting popular a couple years ago, and I get it, there are some brilliant TikToks out there. But again, it’s a specific kind of performance. I think there’s potential for radical undoing in any kind of performance, but I think there’s also radical destruction of certain creative forms. I’m hopeful—there’s some funny content that can be quite upending in terms of how we think about and interact with the world.

I feel we’re constantly living in this moment of intense repetition. It has something to do with why this generation, mine and yours, can’t sit through a three-hour movie, but can sit through a twenty-hour binge-watch of a serial show. We’re drawn to these long, nearly unending series, and I think it’s symptomatic to this characteristic of constant inundation, of different forms of repetition, whether that be memes or TikToks, or even checking out Instagram every day. Even with our special customizations on everything, it’s quite redundant.

This is related to my impulse of creating hybrid texts. I’ve always been interested in creating multi-faceted books, and I think it’s more accurate to what our contemporary reading practices are these days. We’re constantly overwhelmed with information that we can’t ever entirely be complicit in what we consume. Nobody has the attention to absorb and think about everything we expose ourselves to. There’s no way to get around it, unless you completely shut yourself off from the world, which is such a small demographic, and probably one of privilege.

BG: What is your go to movie—the movie that you watch for comfort—and what’s your favorite scene?

JQS: I love horror movies. They’re usually my go-to. My embodiment of the spectacle. Horror movies, on the surface, are so low-brow, simple, gruesome, or grotesque. But I love them because there’s a world, where even though it’s absurd or there’s terror involved, some play of imaginative justice is always involved. I’m thinking about Final Girls. Maybe it’s the permutation of horror tropes, but I love horror movies.

I like the 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later movies. There’s the inversion of the mall setting that’s dying, this 90’s symbol of late capitalist consumption while people are literally eating each other. That’s poetry.

BG: One of my favorite components of Savage Pageant were your illustrations; I enjoyed sitting with them, processing, admiring how they were structured. What does your illustration process look like? How do you decide what to draw?

JQS: For Savage Pageant, I had an editor that suggested to include captions under each image, which I declined. I wanted the images to play with that important oscillation in the book between meaning and meaningless, chaos and connection. I worked off photographs from that Jungleland book I mentioned, but I didn’t want to solely focus on Jungleland. There’s the illustration of the Walmart employee, of Carhenge. I wanted to bring in other cacophonous images and information; just having Jungleland images in my mind would’ve been too on the nose. I wanted to provocatively mince different forms of spectacle to make a comment that this is related to so much of our culture. I’m obsessed with this once place because it relates to everything and how we arrange history.

BG: Your text pushed me to inspect everything in my life and assess its spectacle-ness, kind of like combing through a kid’s head for lice. Like, is this a spectacle? Am I a spectator in this?

JQS: There are so many opportunities to be a consumer of spectacles. This is what I wanted to resist. I finished my second full-length book, which is about my mother, but there are questions about the spectacle there, too. Spectacle of trauma, of war-time violence in Vietnamese culture and diaspora. I find that sometimes artists get into a trap of writing about trauma for audience consumption. Even unintentionally. Written for a white audience, in my mind, to consume different forms of war-time trauma. That’s very dangerous territory.

BG: It’s like having to showcase your struggles, whether generational or current. Putting it on a platform for someone to read.

JQS: I feel that’s the beauty of poetry and poetic texts. When people first start reading poetry, they’re like, I don’t get this. This is hard. I don’t know what this person is trying to say, why don’t they say it more clearly? But when you’re talking about historical trauma, racist violence, American entrepreneurship, you sometimes shouldn’t (re)present it in a way that is linear, with an easy lesson that makes an audience member feel good about themselves. There’s a way of recuperating—speaking of ghosts—that very violence you’re trying to reveal in doing so. Poetry can disrupt the pleasures that a linear prose text affords. When you’re talking around trauma and war, you’re getting into loaded power dynamics of the gaze, and you risk evoking pleasure while reflecting a charged moment.

BG: You mention in your biographies that you’re a cat lover. Do you have any cats? What are they like, what are their energies?

JQS: I have a cat named Kiki, she’s eight or nine years old, and I got her from a pound many years ago. She’s normally around but I think she’s pissed at me today. I grew up with cats and dogs, and I’ve always been an animal lover. Kiki’s vibe is hilarious—she’s a dilute, long-haired tortie. She’s so vocal and inquisitive. I love her, she’s my familiar.

Bri Gonzalez is a Chicana/e queer poet and MFA candidate at the University of Colorado Boulder. They are currently writing a poetry collection on mental disorder representation in pop culture. She enjoys binge-watching horror movies with her cat, Dahlia.

Jessica Q. Stark is a California-native, Vietnamese American poet, editor, and educator currently living in Jacksonville, Florida. She is the author of Savage Pageant (Birds, LLC, 2020), which was named one of the “Best Books of 2020” in The Boston Globe and in Hyperallergic. Her poetry has most recently appeared or is forthcoming in Best American Poetry, Poetry Society of America, Pleiades, and elsewhere. She will be an Assistant Professor in Creative Writing at the University of North Florida this upcoming fall.