Ben Tran: At one point, Nguyệt says of Calder: “I think maybe his artworks were about air raids and bombings.” What is it about aerial warfare that is so haunting to you?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: I’m actually more interested in the ‘live’ and potentially (still) catastrophic memory of war that lies just beneath the surface of the ground in this central region in Viet Nam and less interested in the aerial aspects of the bombardments that caused this situation where UXO [unexploded ordnance] still litter the land and create various dangers and obstacles for locals in that region. So my interest is much more located in the aftermath rather than in the bombardment. With that having been said, I would like to remind people that three times more ordnances were used during the U.S. war in Vietnam than WWI and WWII combined. That was the “technological advantage” that was supposed to win the war.

This idea of trauma is also interesting. Like the landscape in the way that the damage isn’t visible or apparent, the trauma here lies below the surface which is especially haunting and deleterious precisely because it’s not visible. PTSD is a very new concept in Vietnam, as with most parts of the world. But we know that there is much trauma here from the centuries of colonialism and warfare and migrations. Civil war is intensely traumatic. The visuals of the landscape offer us a way to think about these hidden and underlying traumas that still haunt us today.

Ben Tran: Objects and replicas have significant meaning for you. Through them you work as both an artist and a storyteller. Unburied Sounds tells the story of old bombs and artillery shells being reincarnated into objects of everyday use (such as flowerpots and shovels), forms of art, and then a medium for healing. Can you comment on the reincarnations of objects and how “artworks have a different life,” as Nguyệt, the film’s protagonist, puts it? And why are replicas, contra any assumptions that they’re merely reproductions, so important to you?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: Objects contain stories. Or another way of seeing it is that we imbue objects with stories, with meaning. It’s through the excavation of objects that we try to piece together some sort of story of human existence. For me, objects, particularly the objects left over from conflict and war, offer us a way to think about transformation. The power to take something that was meant for destruction, harm, and change it to something that has the possibility to heal is tremendously empowering.

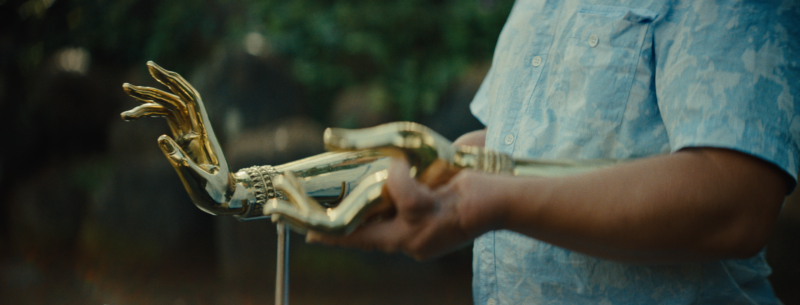

I’m thinking more in terms of reincarnation, both material and spiritual. The material ‘reincarnation’ of the bomb metal into Calder-esque plate bell sculptures parallels the journey of the main character, Nguyệt, as she discovers that she is the reincarnation of Alexander Calder and finds ways to use sound to help her mother heal. I wanted to make visible the parallels between the material and the immaterial, between the ends and the beginnings, between the causes and the consequences.

Making replicas, for me, is a process of maintaining memory. It gives objects life. Remaking creates a cyclical process. And the process of remaking is the process of archiving. It’s like telling a story over and over again, or telling a story to your child who then tells a story to their children and so forth. Things continue to live.

Ben Tran: Unburied Sounds add to Calder’s anti-war politics the crucial dimension of sound, particularly for healing. So the politics and the sound are “unburied”—not necessarily to be unearthed or exhumed, but rather to be recognized and registered for different potentialities. This leads us to the title: “Unburied Sounds.” What is the significance of the “unburied” and of sound for your work? What do sounds index that images or texts might not?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: When thinking of sound, I can’t help but to immediately think of human utterance. Listening to our elders speak and sing as babies is our initial interaction with storytelling and emotions. Sound operates at a register that is more bodily than image and text. We are an ocular-centric society, obsessed with images and with the notion that “pictures are worth a thousand words,” but in fact, everything we see never tells us the whole story. Sounds are never dead. I think of the stories of resistance stories told that are told from generation to generation even in the face of oppression and violence. I also think of simple phrases like, “I’m sorry,” or “I love you,” or “I care for you” that get lodged in parts of our being from years of tribulations or trauma–phrases of empathy and care that can be unburied.

Ben Tran: I loved the soundtrack to the film, which was also the soundtrack of my childhood. Why was it important for you to incorporate songs, such as Trịnh Công Sơn and Khánh Ly’’s “Một ngày ̉ như mọi ngày” or their “Đại bác nghe quen như câu dạo buồn”? There is also Gamelan Salukat’s music in the “Boat People” video that you’ve called the film’s “pulse.” The dead need music, as The Propeller Group has suggested, but it seems that the living need music too.

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: The living definitely need music. As we know deeply, not only are songs strong forms of storytelling, but they have the potential to be piercingly political.

During a time when war was pervasive in a divided Viet Nam, while the majority situated on both sides of the DMZ believed war was the only resolution to the political differences, Trịnh Công Sơn’s music stood out as important social commentary, urgently advocating, urging for peace. His music was poetic and compassionate, and it definitely had an effect on the youth of that time. I fell in love with his music in my early 20’s because of their sounds, but only began to understand their political relevance years later. I’m sure you’ve noticed how often I use Trịnh Công Sơn’s music in my work. Sometimes they punctuate the narrative, like “Đại bác nghe quen như câu dạo buồn” was used in a two-channel that documented the disposal of a 1 one-ton 16 inch 50 caliber projectile in Quảng Trị in 2021. Other times the music has a direct connection to the place in which I’m filming. “Biển Nhớ” was played over the loudspeakers at the refugee camp on Pulau Bidong each time a new boat arrived on the island or when boats taking refugees departed to the Malaysian mainland on their way to being transported elsewhere. In The Island the main character begins to sing that song as a way of remembering the ‘memory’ of that song. So that song was very tied to that specific place during that specific time.

Ben Tran: For all the historically rootedness and object-oriented aspects of your work, your films are not documentary and historical, but then again I don’t think “fictional” aptly describes the narratives either. Perhaps more fitting is “imaginative realities.” Can you say more about the relationship, or even tension, between history and creativity?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: I grew up, and I think most of us are in the same boat, constantly feeling betrayed by the history taught in textbooks. History was my worst topic in school. But when I started to realize that history is made up of fictions that could be challenged and destabilized, I became quite interested in history.

Also while growing up and listening to stories, mostly from immigrants, I started to notice a lot of “what if this happened instead?” or “it’s a shame it didn’t happen this way” or “things would be so different if….” This opens up a space to speculate on possibilities. And it’s different from nostalgia because nostalgia is so set on the past being the past where these ‘speculations’ were about the past leading to different futures. I believe this is my entry point into thinking “speculatively”. I also think that refugees exist in the space of “speculative futures” as they leave things behind and embark on unknowns. It is the speculation of future potentialities that move them forward, and there’s so much creativity in that space.

Ben Tran: I find this idea interesting: that refugees exist in speculative futures–as subjects of possibility, of contingency–which for you is more productive and hopeful than getting mired in nostalgia. (I understand better now the futurity of the “boat people” in your film, The Boat People.) Can you say more about refugees as subjects of the future, rather than subjects in marginal or liminal spaces?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: It is the imagination and desire of future time/space that propels the refugee. “Our ghosts exist in the future,” says the last man on Earth, the protagonist in a film called, The Island, that I made in 2017. This character, teetering on the edge of humanity’s future end, managed to survive multiple apocalypses because he lives on an island called Pulau Bidong – once the largest and longest-running refugee camp after the end of the war in Vietnam. I mention this because it was actually that project that began my thinking of the refugee space as a space of speculative futures. Refugees are jettisoned into liminal space. But beyond being spaces forgotten, liminal spaces can be spaces of transformation, spaces of becoming. And when, in those spaces, we turn our memory towards “speculative futures” is, as you’ve mentioned, a more productive and empowered space. When refugees are driven, both literally and figuratively, to the margins, they are stripped of any agency, but when those marginal spaces are redefined as spaces of ‘speculative futures’ agency is reclaimed. And ultimately for me, it’s about agency.

Ben Tran: Your work puts things into motion, propelling the past into the present and the present into the future. What is the significance of films in setting your artworks into motion, into a narrative? Do the art pieces, such as the replicas set afire in The Boat People, take on a different life?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: It’s funny and charming to look back and realize that I’ve inherited a bit of my grandmothers’ animist beliefs–that objects have souls or spirits, that they are alive. The narratives in the films, just like the stories that my grandmothers’ told me, breathe life into the objects–they situate the object with history and purpose. Oftentimes the objects in my films occupy roles as important as the main human characters. The narrative and the objects go hand in hand; without the narratives, the objects don’t have that ‘charge’ and without the objects, the narratives don’t have a structure on which to cling to. For me it’s important to have the physical presence of these objects in the exhibition space. In relation to the film, it grounds the experience and creates a more immediate connection to the narrative.

Ben Tran: You’re also invested in the agency of local people in the areas where you work. These efforts to convey the lived experiences of war on the ground, in local communities include intimate collaboration with residents of these areas. This is most apparent with the films’ actors, such Hồ Văn Lai from Unburied Sounds. Can you talk about his story, your story with him, and his involvement in the project?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: Hồ Văn Lai is a special person with a special story. I met Lai on one of my very first trips to Quảng Trị. Lai is a survivor of UXO. Specifically, it was a cluster munition that exploded and destroyed his limbs and most of his sight when he was 10 years old in the year 2000. He is the epitome of resilience and positive thinking and has become a sort of spokesperson against cluster munitions, which are banned throughout most of the world because of how inhumane they are, except in the US, China and Russia. He plays himself in the film and he works at Project Renew (an NGO that engages in demining activities) where he teaches school children UXO awareness and safety. Lai and his story were a driving force behind the film.

Ben Tran: So much of your work is rooted in the history of a place, such as Quảng Trị in Unburied Sounds of a Troubled Horizon and Bataan in The Boat People. Even more so, both films feature history museums as spaces that collect and educate through objects and narratives about the human suffering from war and imperialism. What are the differences for you between history museums and the art museums or gallery spaces that might exhibit your art?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: History museums, for better or worse, have agendas. The museums in Vietnam and especially in Quảang Trịi also tell the story from a very specific point-of-view. Art museums also have their agendas, but more often than not, they tend to be more spaces for critical dialogue. History museums often have an aura of sacredness and of being definitive, whereas art museums and galleries counter that, by prioritizing experimentation, defiance, and dialogue.

Ben Tran: Unburied Sounds features the Quảng Trị accent, with all the mi-ing and mô-ing. This leads me to a question about linguistic and cultural legibility. In The Boat People the main character and the main object, the head of a statue, speak to each other in different tongues. In Unburied Sounds the dialogue is strictly in Vietnamese, with a Quảng Trị accent. There are subtitles for an English-language audience, yet the accent would not be detectable to a non-Vietnamese audience. How do the linguistic differences of Southeast Asia factor into your work, and what does it mean for your films to address an English-language audience? (I ask this, in part, because of the English textbooks in The Boat People.)

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: I definitely don’t want to make work that only addresses English-speaking audiences. Language is access and language is instrumentalized as a tool of power. This was my thinking behind the English textbook references in The Boat People. There’s a scene in The Island that re-enacts and inverts an interview between an immigration officer and a refugee where I was also thinking about language and power.

As storytellers, we have to attend to the specificities of place and of people. In making Unburied Sounds, it was important for me to showcase the Quảng Trị accent, which even in Vietnamese media doesn’t get much representation. This accent is something that only Vietnamese speakers have access to. Ironically though, even Vietnamese-speaking viewers, not from Quảng Trị, who have seen the film have expressed to me their need for subtitles. These levels, or layers, of specificity are important to my practice because they show the complexities of identity, place and, history. Southeast Asia is a complex space with such diversity in regards to cultures, languages, and histories. To simplify those into a general or simple notion of Southeast Asia would be detrimental to those dimensions.

Ben Tran: This leads me to our concluding question. The issues central to your work exceed topics often associated with questions of diasporic identity—although you were trained and educated in the US. How would your work be different if you lived and worked in the US? Or perhaps a better question, how has your work been informed by living and working in Sài Gòn and Southeast Asia?

Tuan Andrew Nguyen: It may seem that the answer to your question is in the question itself. Moving my practice away from the US helped me to think beyond my own migration, beyond the Vietnamese migration to the US. It also helped me to think outside of the US and to see the larger effects of colonialism more clearly. Which then allows me to make connections between communities and events that may seem disconnected through space and time.

Ben Tran: Thank you for your time, Tuan, amidst all your travels.

Ben Tran is an Associate Professor at Vanderbilt University and is a Contributing Editor to diaCRITICS.