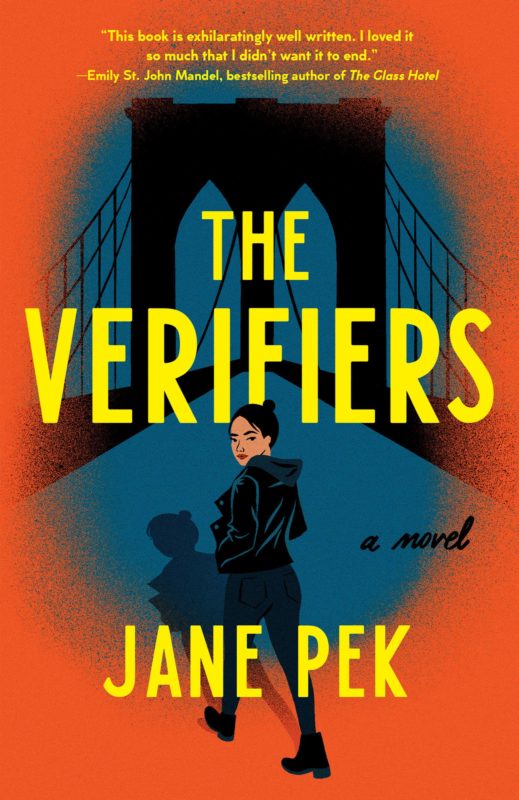

Deputy Editor Sydney Van To talks to Jane Pek about the detective story, the future of technology, and our social structures. Jane Pek’s debut novel The Verifiers is out now by Vintage/Knopf.

Sydney Van To: The Verifiers rejects the white male detective tradition and is part of this recent Asian American recuperation of genre fiction. As someone writing an Asian American queer feminist novel, what is the detective story doing for your book?

Jane Pek: I’ve always been really interested in the idea of the detective as a character. That there is some unknown, some mystery, some secret, and the detective can put together the clues and uncover the truth. Literary fiction has that kind of character as well, such as in the works of authors like Haruki Murakami, Jorge Luis Borges, Robert Bolaño. My original approach to The Verifiers was more centered around the mysteries of love and relationships rather than a murder: “Why would someone cheat?” or “Why would someone conceal something about themselves?” But I felt like these mysteries were not generating enough narrative momentum, so finally I decided to try killing someone off. Solving that murder then became the narrative engine of the novel.

Murder mysteries, as you say, are white- and male-dominated. I grew up reading Agatha Christie and Arthur Conan Doyle; later, Georges Simenon and Josephine Tey. For me, the character of Claudia came first. I had always wanted to write a gay female because growing up, I had never come across these types of characters. I wanted a gay female character who is out there, having adventures, doing these things which are unexpected for someone like her. To be honest, I was hesitant about also making her Asian. When you write a minority character, you worry that everyone will think, “Oh, that’s you.” Those sorts of concerns about being pigeonholed. But ultimately, I had a clear sense about who this character was, and it was that she is a Chinese American, second-generation immigrant, and because of that, she viewed the world in a particular way. Setting it up that way, the way she moves and thinks is necessarily informed by who she is. This isn’t a novel about Asian or lesbian identity, but about someone who possesses these traits, and you therefore see the world from their perspective.

Sydney: I like this description. The evolution of the detective story had begun in this rationalist, deductive mode with a genius mystery solver, but then it moved into noir territory, where more social forces are shown to be at work. The detective becomes immersed in the world as a particular subject, rather than as some detached observer. One thing I see you saying is that, the subject’s worldview inevitably influences how the case is solved, and that is where the politics of representation comes in, while avoiding a kind of pedanticism.

In particular, I’m thinking about the importance you’re giving to adventures. Another benefit of the detective novel is that it allows a freedom of movement which is often withheld from women, queer people, and Asian Americans as people vulnerable to these repeated acts of violence and social exclusion. To say nothing about the toil of a full-time job: I mean, who has the time or energy to go on adventures? The adventure of detective fiction might be a utopian response to a society which surveys, polices, and works certain populations.

Jane: It is a genre which allows the story to be larger than life, while remaining consistent within that story’s universe. Given the rules of this genre, it is within the realm of possibility that Claudia can randomly walk into a job as an online dating detective, and then have one of her clients go missing, and so on. You read because you want to have these adventures yourself. Claudia is a voracious reader, so it plays into why she would want to go deeper and try to uncover this mystery.

Sydney: If we were to be demeaning about literary fiction, we might repeat what one of your characters Lionel, a white male MFA-trained writer who is interested in books “where nothing happens.” But then it is revealed that he’s been ethnographically exploitative and using the immigrant family drama of his Asian American girlfriend as writing material. It’s because the white perspective is exoticizing that Lionel can remain so interested when “nothing is happening,” just as long as this “nothing” concerns racial minorities. Hence, your endeavor to reclaim plot as a way of resisting the expectations for Asian Americans to write or be written about in a realist mode.

Jane: I did an MFA, and I really loved it. But for many of my instructors, plot wasn’t that important; the really important things were language and character. I make fun of murder mysteries, but I also poke fun at literary fiction through Lionel. A story which is plot-driven can be reclaimed as no less worthy than anything else. There’s a lot in literary fiction to be impressed by and moved by, but I always felt like genre was slighted and dismissed in the MFA context. I wanted to write a story that combines genre elements while addressing issues that we think of as “literary,” and also having Claudia be aware of all this.

Sydney: You have an MFA, but you also have a JD. How did that shape your writing?

Jane: I went to law school right after college and became a mergers and acquisitions lawyer (like one of the characters in my novel actually) at a big law firm for five to six years. I took some time off to do the MFA, but then I got concerned about financial security and immediately ran back to the comforts of corporate law. During the JD, I was just reading cases, analyzing, absorbing all of that. I felt the same way with the MFA. It was this period of time where all I needed to do was focus on reading, writing, and getting better at this craft of fiction. I definitely appreciated the MFA a lot more, having worked as a lawyer beforehand. It felt like such a gift to have all this time and space, both physical and mental, to write, to not think about anything else.

The legal training influenced The Verifiers because a lot of the novel is about tech, data privacy, and the uses of data collection. I hope that I was better able to write about these concepts because I had thought about these from a legal perspective.

Sydney: Maybe this could move us into one of the philosophical questions that I saw as being framed in your book. You deal with this paternalist and utopian desire to program human behavior toward higher aims and the increased satisfactions of our desires, which is the way your character Komla thinks about dating apps. For him, dating apps can incentivize you into becoming a better person and match you with the people you’re supposed to match with. In contrast with that, we have something like a liberal humanist attitude which emphasizes individual agency but which might also be technophobic. How does your book work through these positions?

Jane: I think that’s a good way to put it, and very balanced in framing the two sides of the debate. There is a tendency right now to be anti-tech, focusing on all the terrible things that tech companies are doing to us. I don’t want to come down on one side or the other because I’m still figuring it out. In The Verifiers, I wanted to present a well-thought and well-argued perspective via Komla and Lucinda who are the believers in tech. At the same time, I wanted to highlight the fact that we do give up a lot of our data as a trade-off for convenience and efficiency. A lot of the time, we don’t think about this because we only see its immediate benefits. Google Maps, emails, Zoom, social media. They’re all free, but then again, they’re not. In order for the company’s business model to work, they have to find some way to monetize what they’re providing you.

This is just to acknowledge that this is the way we have set up our society to run. Even if an individual wanted to opt out of it, you can’t really. In the last few years, there’s no way to get around without a phone. For instance, in Singapore where I am originally from, in order to access indoor spaces during Covid you had to tap in and out using your smartphone. Then there are places which are increasingly requiring contactless payment. We are moving along this path such that it is harder and harder, and maybe not fair to say to individuals, “If you don’t like it, just opt out.” As a society, we need to think about how we want to structure these new arrangements between us and these companies that have so much information and power. What we are seeing now is all new and unprecedented, and we are having to make it up as we go along: what role the government should play, how much freedom tech companies should have to operate. I tried to use online dating as an arena for talking about these ideas, but they could really be applied to all areas of our personal and social lives to the extent that we rely on technologies to mediate all of that.

Sydney: The detective form helps you with these because the detective is always looking for a bigger and bigger structure. The way I had originally posed the question is perhaps not attentive enough to structures. The idea of freedom for the humanist is already presuming a particular arrangement where you can make use of your freedom. These apps, institutions, mapping, and protocols have already been put in place for you, and you want to remain blind to it so that you can continue to assert this idea that you are free. Whereas the paternalist attitude is blind to the hierarchies and inequalities which it has set up: who is benefitting and who gets to decide on these arrangements. The geographic terrain which your protagonist explores expands into a social terrain.

Jane: It does get a bit scary because if you zoom out far enough, you realize, oh my god, everything is being controlled. The book gestures toward that: how much of what we think are our own thoughts, and how much of our decisions are our own decisions? How well do we really know ourselves? When we think we want something, do we really want it? A lot of contemporary tech is focused on helping you make better decisions by knowing you better than you know yourself. But correlated to that, are they really helping you figure out what you want, or are they guiding you to want what they want you to want? You are defaulted to see what they have recommended. This applies to what you said about structures. In a sense, all the decisions we make are a function of the structures around us. What does freedom actually mean, then?

Sydney: Yes, but you want to stay in the impasse, or at least your novel does. You don’t want to give up the idea of freedom because you are also giving up the critique of inequality and power. So now we are thinking about the masks we wear. This theme lets you juxtapose the family storyline alongside the professional and romantic storyline. Masks are all around us. Although Claudia is focused on the masks we wear for our dating profiles, she comes to realize that she still wears a mask around her family, and her family members are also wearing their masks around her. I don’t think this is necessarily a malevolent thing in your book.

Jane: I like your metaphor of masks, but I had not thought about it through that metaphor. One part of the question, “What does it mean to know a person?” is “Is there really one coherent person to know?” We are all different around different people in different contexts. Arguably, Claudia is less “herself” around herself because she has to conceal the fact that she is gay from her mother, and she has to abide by certain expectations that her family has of her, which she herself does not actually want to follow. But in other respects, maybe this is her truest self because they are the people who are closest to her, in a specific sense. The novel is interested in asking “What does it mean to know other people?” and also “What does it mean to know yourself?” Both of those questions are developed on the personal level for Claudia—what she learns about her siblings, and how her perspectives of them change and develop—and what she learns about the people that she’s verifying—how her initial assumptions about them turn out to be either wrong or incomplete or misguided.

Ultimately, it is a question of knowledge and the limitations of how much we can know. Given all these personas that we have, online and offline, and given how much of how we act are dictated by the expectations of others, how much can you actually know what you really want, as opposed to what you have been socialized to want? At one point, Claudia has a revelation about her brother: that maybe the way he cares about her isn’t just, “I love my sister and I want to do everything for her,” but that it had come out of a place of necessity. The end result is that he does care for and love her. But what does it mean that it only ends up that way because of the original circumstances requiring that he take care of her?

Sydney: I guess this is another way of repeating the question between paternalism and autonomy. Some political theorists think about the process of civilization as putting on a mask. For example, Hobbes says that if we are left to our own devices, we would be ruthless and murderous, but that we restrict ourselves from these impulses so that we can live together. But we have to ask, where do these masks come from and who put them on us? For Claudia, the mask she has to wear to conceal her sexuality from her family is not a good mask. But for Charles, the mask which compelled him to take care of his sister is maybe not a bad mask. So I guess our conversation is moving toward a more sophisticated understanding of intimacy, just as we need a more sophisticated understanding of freedom as not just totally absolute and detached from social structures. So too with intimacy, it would be a function of the different social contexts that we find ourselves in.

Jane: Yeah, it comes back down to structures again. What are the structures which shape our behavior? Out of personal interest, I’ve done a bit of reading about how we think about the brain and free will. Our neurological processes are a structure too. It’s coming out more and more that what we think of as our own decisions are mediated by the chemicals in our brains or the way our synapses fire. Is this freedom as we have traditionally understood it, or are we just compelled by our genetics? I will say that structures shape a lot of how we think, act, and behave. But being an optimist, I like to think that there remains some kind of agency. When we think we are choosing to do this one thing, even if it may have been influenced by structures, there is some value in our making that choice.

In The Verifiers, the limitation to these dating platforms which promised to find your perfect match is that they were being fed imperfect data. The users were giving the data they wanted to give, and these users might not know what they themselves wanted, or felt that they had to say certain things. One thing which I might explore in a future book is: what if the algorithms actually did get really good at predicting who we should be with? Does that mean we should just go to the algorithms and just key in our information and get matched up with our perfect significant other? Or does that take something important away from us, in terms of choice?

Sydney: That would come from a very means-end conception of desire. I feel like desire is just a much weirder phenomenon. It’s not just that you have a desire for some concrete thing which can be directly fulfilled. It’s not even that your desire, albeit unknown to yourself, is a blank which can be adequately filled in by some algorithm. I think desire tends to be propelled toward the thing which is always out of reach or the thing which can never be formulated. Maybe desire is not something that you can ever have a perfect object for.

Jane: Those are very true ways of looking at desire. At the end of the day, technology still cannot get us all the way there. We still have to make our own mistakes.

Jane Pek was born and grew up in Singapore. She currently lives in New York, where she works as a lawyer at a global investment company. Some of the things she’s into: picking up different martial arts, reading coming-of-age novels, watching contemporary theatre, and cycling around the city in search of superlative almond croissants. The Verifiers is her debut novel.

Sydney Van To is the deputy editor of diaCRITICS. He is currently a PhD student in the Department of English at UC Berkeley, with research interests in Asian American literature, critical refugee studies, and genre.