While reading She is a Haunting, Trang Thanh Tran’s debut novel, I recalled a short song that my mother taught me as a kid:

“Cái nhà là nhà của ta

Công khó ông cha lập ra

Cháu con phải gìn giữ lấy

Muôn năm với nước non nhà.”

My mother was passing on a joyful song that she and other kids clapped along to in her childhood days in Vietnam. The song roughly translates to “This house is our house / With hard work, our ancestors built it / Descendants must steward it / Year after year upon this homeland.” It’s a song that pays homage to our ancestors, and enthusiastically takes up the duty to preserve the fruits of their sacrifices. The house in the song can be a literal, physical house. It can also represent a home, the relationships within a family. Nationalistically, the house can also symbolize the nation of Vietnam, the last line referring to the mountains and the sea.

Like the song, author Trang Thang Tran makes multiple meanings of a house, with an eerie twist. At the center of She is a Haunting is Nhà Hoa, or “Flower House”, a 1920s villa built by French colonizers in Đà Lạt, and abandoned by the French and Americans after the Vietnam War. Seventeen-year-old Jade Nguyen reluctantly spends her summer before college in the villa with Ba, her father, who has been renovating the place into a bed-and-breakfast. Jade’s younger sister Lily also stays with her and tries to de-escalate Jade’s antagonism toward Ba; Jade has not forgiven him for leaving her family behind for her mother to raise all alone. She would prefer to never see him again, if not for Ba’s promise to pay for her UPenn college tuition if she helps him design the bed-and-breakfast website.

Even without the supernatural elements in the novel, Nhà Hoa is already a haunted house, an eerie setting that illuminates the taut dynamics of a Vietnamese American family plagued by guilt and regrets, and the history of French colonial violence in Vietnam. The history of Nhà Hoa’s occupants carry personal significance for Ba. Ba’s mother had grown up in the house with her family, who attended to the Dumont household—the French owners of the villa—and lived in the servant’s quarters. Although Ba himself never grew up there, he grasps onto a narrative where he owns the house his ancestors served in, to absolve the regret he feels for not being at his mother’s deathbed in Vietnam when he was making ends meet as an immigrant in America. I imagine Nhà Hoa orchestrating its own version of the song my mother taught me as a kid, in a creaky, torturous loop, as it possesses Ba to overwork himself and renovate it, taking advantage of Ba’s familial guilt to fulfill its greedy wish of being lived in again, and even claim lives.

Nhà Hoa unsettles Jade’s family not just because of its creepy noises, gruesome bugs, and ghosts. Rather, horror in She is a Haunting operates by taking familiar themes of identity, belonging, ghosts, family, and culture in Vietnamese diasporic literature and dramatizing, spoiling, or subverting them. For example, every evening at six o’clock, Ba cooks various Vietnamese dishes for his daughters, and the Vietnamese family of three gathers in the dining room to share a meal. It is the idealized “bữa cơm gia đình,” or family dinner, where Ba’s cooking shows that he still cares for his daughters, even if he can’t express it verbally.

But Ba’s complete disregard for Lily’s veganism is not the only thing amiss. There is never a day that food in the fridge doesn’t spoil. A beautiful ghost appears to Jade and cryptically warns her not to eat her father’s food. And while Tran can effortlessly compose illustrious, appetizing descriptions of Vietnamese food, she opts instead to reveal the bugs and parasites that Ba has been adding to his dishes, under the influence of the house’s ghostly owner. Tran offers up Vietnamese cuisine, which foreigners frequently consume and exoticize and even the most culturally disconnected Vietnamese descendent can lay claim to—only to take it away from the reader and Jade’s Vietnamese American gaze before they can be satisfied, emphasizing her dissonance of belonging in Vietnam. The recurrence of the corrupted family meal reaches a climax in a later part of the novel when Jade is so worn down by sleep paralysis, ghosts coming after her, and the house’s violent secrets, that she can no longer heed the warning to avoid Ba’s food:

Crushed crabs, shrimp paste, and fried shallots…

“It’s your favorite,” Ba says from the head of the table. The insulation’s yellow fuzz dusts his brows.

“I don’t want to eat,” I say, yet am beckoned forward…

I sit. The chopsticks are in my hands. There’re floating tomatoes, squishy and juicy, and a broth that’s all red flame in a porcelain bowl. White noodles as pulpy as worms on wet pavement. Pressure-cooked pigs’ feet, the hairs plucked.

“I’m not hungry,” but I eat.

Although Jade knows that her father has spoiled the food, she is ultimately lured by the performance of a happy, functioning family sharing a meal, and, in a more twisted way, the relief of surrender. Like any caring father, her father makes her favorite dish; like the obedient daughter she wants to be, she eats:

Secrets do not keep a girl fed, and this nourishes me. It reminds me of home, Saturday nights in a warm kitchen.

I eat, I eat, and I eat.

The house watches from the wallpaper, buzzing, growing loud, overtaking conversation. It’s always so pushy. I gnash tendons between my teeth. I don’t want to. I’m so hungry. It feels good to not be in control…

Nhà Hoa is ever-present in this family meal. The house’s dust settles on Ba like a hypnotic pollen as he feeds spoiled meat dishes to his two children. The house’s loud, pushy buzzing is its siren song, fulfilling Jade’s longing for a healthy relationship with her father, rather than the brokenness and anger that they have instead, as long as she eats—and readers sympathize with her weariness. Instead of cheerful chatter and the laughter of conversation, the only sounds from the dining room are whimpering and gnashing of meat, and a house that disturbingly recites, “They’re eating this house. They’re eating this house! They’re eating this house…”

As Nhà Hoa was built during colonization, She is a Haunting also forces Jade and the readers to confront what they know of French Indochina, which only a handful of Vietnamese American stories have touched on. In a house with such a violent colonial history, is Jade being haunted by French ghosts or Vietnamese ghosts? What do they want, and what can a Vietnamese American girl like Jade, historically and culturally removed from Vietnam, do for them? Although I was excited for the novel to engage with colonial history from Jade’s perspective, I couldn’t help feeling that the older Ba would’ve been a more effective narrator for this purpose. Much of this is because of Jade’s deeply poignant characterization of her father; despite her resentment toward him, she qualifies his hurtful actions by directly telling readers of her father’s pain, regret, and guilt of leaving Vietnam and family behind for America, and how it came to shape him. As Ba’s violence escalates at the story’s climax, Jade heartbreakingly tells us, “The worst thing is being unsure whether Ba’s behavior is all due to [the ghost Marion’s] influence or his ambition, born out of pain. I can only keep trying.” Tran’s character Ba is among the more complex characters I’ve read in diasporic Vietnamese literature, and one that will continue to haunt me.

Tran is aware that there are limitations to telling a colonial narrative through Jade. In an early chapter, Jade reflects on Vietnam in what feels like an excerpt from a personal essay:

I think of everything I’ve seen in Vietnam so far… History has left its mark among these sights, and erased others. There are streets here named in French; there are universities built by Vietnamese people by the French who commanded them. They’re named in someone else’s honor. Of course, [Nhà Hoa’s investor Alma’s] drawn here, where the past seems rosy and romantic.

But who am I to say? I wasn’t colonized. I’m not Vietnamese enough to have an opinion on anything other than what makes a good banh mi (the baguette) or pho broth (how long it’s been simmering and which bones used)…Here I’m cut too sharp. Here I’m a wound.

Perhaps Jade’s self-awareness absolves the novel from needing to have a deeper message on French colonial history, besides encouraging the younger generation to acknowledge it and call out present-day colonizer mentalities; Jade never returns to this reflection again. But whether or not she was colonized or “Vietnamese enough” ultimately didn’t matter—the house and its colonial ghosts continued to threaten her sanity. Although a bit jarring to the flow of the rest of the novel, the reflection reveals our seventeen-year-old narrator’s seriousness and maturity. Jade Nguyen is overburdened already with identity and family issues, and contemplating her place in colonial history and hauntings add more to her plate. As a Vietnamese American daughter shouldering my own familial responsibilities, I see how Jade has been forced to confront her greatest fear throughout the novel—the horrifying belief that she is causing her Vietnamese immigrant family suffering and shame.

Jade has already hurt and lost her best friend in the process of hiding her queer identity, and fears coming out to her mother. She’s tormented by guilt as she watches her mother return to Vietnam for the first time after years of overworking herself at a nail salon; her mother would’ve been able to enjoy this much earlier, if Jade and her siblings weren’t such a burden. And ultimately, how Jade and Ba’s relationship collapses in She is a Haunting is the young adult horror antithesis to the “millennial parental apology fantasy” subgenre that Vox reporter Emily St James coins for the arc of recent immigrant and queer narratives like Turning Red and Everything Everywhere All at Once. Parents in Turning Red and Everything Everywhere All at Once realize and apologize for the personal trauma they’ve inflicted through the way they raised their children. They accept their children, and this understanding ends the cycle of intergenerational trauma. In contrast, Jade and Ba’s relationship goes up in flames with stubbornness, guilt, and blame despite Jade understanding his intergenerational trauma. There are no apologies; Jade bears it when her father blames her for why he left the family.

As a teen narrator, She is a Haunting’s protagonist Jade will feel familiar to YA fans, especially readers of Asian American young adult subgenre. Tran makes her debut novel more impactful by getting creative with the idea of horror as corruption of care in a Vietnamese American household. There are times when it becomes difficult to keep track of how Nhà Hoa’s haunting, its history, and its ghosts complicate or have anything to do with Jade’s mountain of personal issues—but Tran’s scenes are rich and powerful, offering so much for readers to think through. She is a Haunting is a fun, thrilling, heartbreaking YA horror novel that is a Vietnamese American story through and through, inextricable from every plot element.

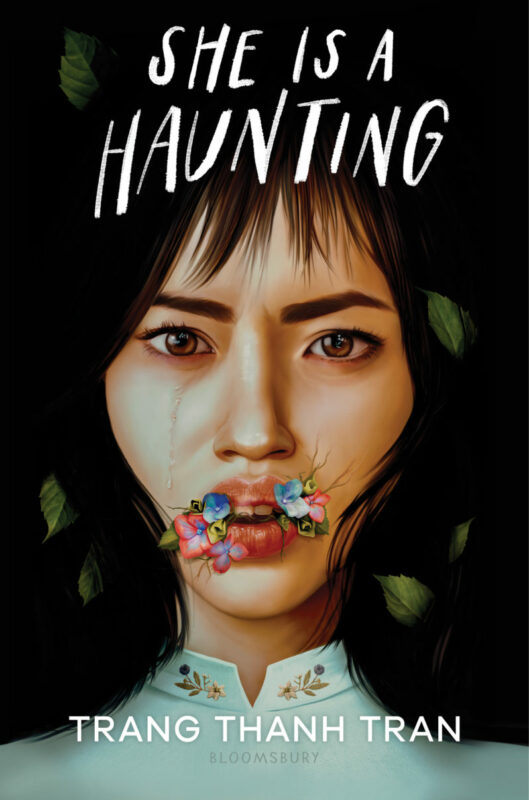

She is a Haunting

by Trang Thanh Tran

Bloomsbury Publishing, $18.99

Cathy Duong is a current junior at Yale, majoring in English. She enjoys (over)analyzing all things Vietnamese, from the briefest references to Vietnam in Western pop culture, to art, literature, and film created by the talented Viet diaspora.