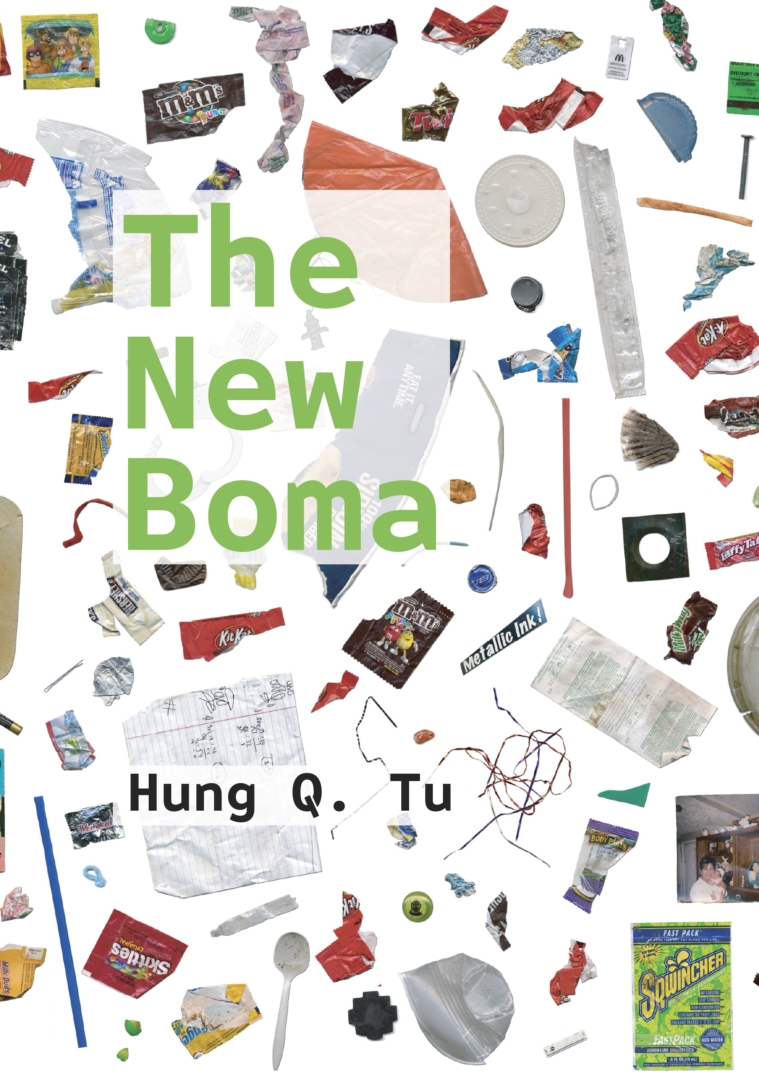

Deputy editor Sydney Van To talks to Hung Q. Tu about San Francisco, the postmodern present, and capitalist ideology. Hung Q. Tu’s poetry collection The New Boma is out now by Dogpark Collective.

Sydney Van To: It has been almost twenty years since your last book, which is one of the largest gaps I’ve ever seen in a poet’s career. And now you already have another manuscript so soon after The New Boma. What is the reason for your return to poetry, if it’s accurate to call this a return at all?

Hung Q. Tu: Much had to do with physically leaving San Francisco and the poetry scene in the early aughts. That was a period of extreme gentrification where block after block was seemingly falling to this phenomenon as if they were dominoes and I found myself among the casualties. Looking at where San Francisco is now, those days seem rather leisurely in its pace. But I never stopped writing, just thinking the work would remain private. The opportunity for publication was a bolt from the blue when Caleb Beckwith (the publisher) just literally happened to come across proofs for some poems that I published in a journal his wife was type-setting. And the rest, as they say, is history.

SVT: Compared to your earlier two collections Verisimilitude and Structures of Feeling, the poems in The New Boma tend to be shorter. In some ways, this is a facile distinction because most of your poems still have the same pacing, namely, a rapid-fire series of jokes, remarks, rhetorical arguments, or as you call them, “toy poems.” But now, you seem to want to get to the punchline faster, and these punchlines also land heavier.

HQT: Compared with The New Boma, the earlier work, as I remember them, are less disciplined and more of a stream of loosely related critiques and rawer in its emotion, whether amused or more often, disgust. The New Boma, especially the blockier poems, works behind an affected persona. At the same time, the work is more straight-forward and more concerned with meaning (whatever that means).

SVT: I also found that the affected persona of The New Boma made the poems more comprehensible, at least on my end. What kind of persona is this?

HQT: I guess you could say the persona is a simple-minded person, given to shock and surprise. The purpose may be to erase myself to the extent possible and to see things anew while coming from a place of gullibility. In this way, perhaps it disarms the reader a bit and makes the work more approachable.

SVT: A second difference is how they relate to the present. Both are critical of our postmodern experience under capitalism, but The New Boma seems to amplify the bizarreness of the present, particularly through images pulled from horror, science fiction, and dystopian genres. For you, the most disorientating thing is that nothing has fundamentally changed in the last several decades, despite our real experiences of technological and economic acceleration.

HQT: I guess it has something to do with perspective and age. It’s one thing to be living in a transitional moment and another to be a conscious witness to it and pointing to it as if you’re outside of it, as you’re going through it and looking at it presently as well as retrospectively. This dual perspective turns into a kind of vertigo and maybe that’s where the comedy comes from. An incredulousness that I’m actually living through these utter absurdities.

SVT: What makes you feel like you are living outside of the present?

HQT: Not quite outside the present, but a sense that while I’m in the moment, there’s also already a future retrospective looking back at this present. Anticipating an awareness of the now, as it’s happening. It’s a conceptual habit stemming from having lived through a present-past, if you will. A lot of this anticipation (read: anxiety) concerns technology, which I must admit, scares me to no small extent.

SVT: The tone you adopt in this collection wavers between being glib and synthetic. This ambivalence is often highlighted by the way you draw upon the inane idioms of our language. You write, “These words could be anybody’s / giving mouth-to-mouth / to a dummy who could be anybody // Number one on her list of turn-offs: superficiality.” The irony is that we cannot not be superficial, or as Zizek would have it, the cynic is the most ideologically interpellated because they believe that they are actually outside of ideology.

HQT: As many Europeans will tell you, Americans seem very superficial and thus disingenuous to them. But I don’t think that’s what you’re talking about. Aren’t cynicism and superficiality both dead ends? That line about superficiality comes from those glossy fashion / lifestyle magazines and their bait-rich covers that have these numbered lists purporting to issue some kind of modern urban wisdom to their dear readers. And the particular line offers a critique of something using that form, but in such a way that it is totally unaware of itself. Sorry if that was a little confusing, but trying to explain a blind circularity leads to my very own blind circularity.

SVT: Those listicles which are so ubiquitous today proceed as if there is some kind of logic to their enumeration, but it only really reveals this fragmentation of thought. Perhaps for you, this is an exemplar of postmodern form. I wonder if you think about tourism in a similar way, as both this futile “search for oneself” and as a meaningless bucket list.

HQT: It’s funny you ask, as I’ve just come back from traveling after a long pandemic hiatus. Traveling is wonderful and those experiences can be so, err, “educational.” But you’re right about your observations. I would add the rather absurd quest for the “perfect moment,” i.e. the obsessions with sunrises and sunsets, etc. And for younger people, a mania for “doing” places and as many places as possible. Perhaps it’s a search for the genuine whatever. It is just ironic that they go about it in the most disingenuous way. In my experience, it’s easy to forget places, but the people you meet are the ones you remember.

SVT: The classic critique of multiculturalism is that it offers surface-level diversity without actually redistributing wealth or power. The “and” of multiculturalism seems like another way of understanding the logic of seriality under postmodernism (or, of global expansion under capitalism), thus ironically homogenizing the subject of identity politics. You write, “the ‘domino theory’ was right after all! / loss of identity and feeling devalued / are just some of the possible side effects.”

HQT: I feel very uneasy and suspicious about the aspirational meme that bleeds into all manner of languages and cultures encapsulated by that word “and”. There is something particular about American positivism which constantly and even desperately needs or wants to reconcile the irreconcilable. I’m thinking of the work/life balance or, more broadly, the self-serving marriage of free market economy and democratic pluralism, an insipid version of “having your cake and eating it too.” This is an ideology which mixes its truth with lies, so that it can be half true while being all wrong. This a thread braiding its way through much of the work in The New Boma and the most recent manuscript, tentatively titled, The Body Politic.

The New Boma

by Hung Q. Tu

Dogpark Collective, $18.00

Hung Q. Tu lives in San Diego, California. He is the author of Verisimilitude and Structures of Feeling.

Sydney Van To is the deputy editor of diaCRITICS. He is currently a PhD student at UC Berkeley, with research interests in Asian American literature, critical refugee studies, and genre.