A Plucked Zither is Phuong T. Vuong’s sophomore poetry collection. Vuong’s poems draw upon her experience as a 1.5 generation Vietnamese American raised in Oakland, California, and echo the familiar themes of diasporic Vietnamese literature, including a meditation on nước as water and nation; watching an immigrant father’s labor and guilt from a distance; and the shame of losing the mother tongue. Vuong’s collection opens with epigraphs from Sara Ahmed and Jodi Byrd about the act of returning, of being in transit and in relation, and how a person can move between space and time from a memory. Throughout the collection, Vuong’s poems flit from one location to another, where preoccupations of the speaker “I” oscillate from that of an immigrant’s, then of a mother’s daughter, a father’s daughter, a granddaughter, a lover, and a poet.

Multiple poems of A Plucked Zither wrestle with what it means to come into English as a second language and to become bilingual. The poem “Fifth Grade English” takes a turn on the school attendance roll call dreaded by immigrant kids by describing a formative moment when Vuong’s name is spoken correctly in her American elementary school:

This the year punctuated, the first

Vietnamese teacher I had (the only)

pronounced my name correctly

even clarified inflections:

Is it Phương or Phượng?

Phương.

So stunned I spoke as reflex.

Fifth grader Phương, acculturated to an American experience of teachers butchering foreign-sounding names, is prepared to respond “Here” to a mispronunciation of her name—to acquiesce in her misnaming. Instead, the Vietnamese teacher recognizes her Vietnameseness. “Phương or Phượng?” the teacher clarifies, acknowledging complexity and multitude of Vietnamese names, of Vietnamese identities. Phuong is “stunned” out of a second nature that acculturates to the majority; her mother tongue “reflex” takes over to respond to a Vietnamese calling.

Vuong expands on the idea of language as an embodied experience later in the poem, when she reflects on what she learned of English from other immigrant classmates during school recess.

other black-haired children in so many accents

taught me:

thirteen not tirteen

library not liberry

Though I still enjoy the hidden fruits in calling it such.

“Thirteen” sits like silt behind my teeth

My wrong sounds

sweeter, more guttural instinct. Yet,

I read this poem aloud

and remind myself

not to fill but feel.

Vuong returns to language as reflex, this time by understanding her English pronunciations to be “guttural instinct,” not a matter of correctness. And above all, what concerns the fifth grader who will grow up to be a poet is whether the words “sound sweet”. Vuong comes into learning English as a second language by collecting “hidden fruits” that only her Vietnamese tongue can taste. She can enjoy learning English as a generative process, indulge in a poet’s pleasure in sound, rather than be embarrassed about mispronouncing things. But the poem’s last sentence begins with “Yet,” signaling Vuong’s ongoing conflict of putting this into practice as she gets older. Taking ownership of English as an immigrant, especially as a poet writing about the complicated diasporic experience, is something she needs to “remind” herself to have courage to do. It is difficult to maintain the playful “reflex” of experimenting with English that Vuong had as a child, and even more so when her growing English skills come with the angst of speaking Vietnamese less and less. “Fifth Grade English” serves as an entry point into how the gap between Vuong’s English and Vietnamese fluency distinctly shapes her relationship with her parents, her grandmother, and herself, explored in the poems “In Which Language Burrows,” “Between Bridges, Bilingual Burnings,” and “What is the Angle of a Rounded Tongue.”

Vuong also experiments with form through her poems with three columns. Taking inspiration from contrapuntal poetry, which itself is inspired by the musical concept of counterpoint, Vuong uses form to channel multiple voices through a poem. “Diaspora is No Way Out” is a three-column poem that compares personal and collective memory to a “basket outside/the body,” woven with fraying family relationships that can be “snipped (jagged)” by intergenerational trauma. The reader partakes in this metaphorical weaving by weaving multiple poems from Vuong’s lines. Each stanza has three lines, with nine stanzas total formatted in three rows and columns. Each stanza can stand alone as its own poem. Each column, and each row, can also be read as complete poems. The last column and the last row share the same final stanza:

| a way of knowing living as if watching | ||

| of course migrant outcome is haunting a wildness circles | ||

| family ties thinned makes sense then become a wisp | snipped (jagged) exits morph we run survive anew | of course migrant release from feeling embodied is trauma |

Vuong reflects on the history of diaspora, of the push factors that force migrants to leave. While we celebrate diasporic communities with narratives of pride and resilience, decisions to leave the homeland and refugee journeys are traumatic. Both poems reach the inevitable conclusion of trauma. Release and refuge from one tragic circumstance, and attempts to protect and sustain family through migration, exist side by side with the loss of identity and family relationships; new wounds manifest in repeated attempts to survive in a new place. The title “Diaspora is No Way Out” asks the reader to meditate on geographical, mental, and temporal landscapes of the diaspora—to consider the great distances that migrants have traveled to seek freedom, but the more time and generations needed to heal from scars and be freed from hauntings.

In the collection’s final poem, Vuong adapts the contrapuntal form to beautifully create intergenerational dialogue between a granddaughter and a grandmother. Reading the left column as the granddaughter’s voice and the second column as the grandmother’s voice, the poem “Grandmother Says: New Theorems” offers the grandmother’s story of survival during the war, one that survives through the granddaughter.

… | i cannot think, starvation in some years a blanket bare protection we kept losing the little we had no time, nor a stretch of land granddaughter |

The grandmother’s poem speaks of tenacious endurance, while the granddaughter’s poem is hopeful as a product of her grandmother and mother’s survival. The granddaughter is nurtured by her grandmother’s wisdom that they always have “options for better/a truer way,” because the grandmother survived the war, despite the little time or options she had then.

Following this section, the granddaughter and grandmother’s voices overlap in a single stanza:

where our shapes intersect

a story of surviving until we’re alive

portrait as a point with vectors

Vuong imagines immigrants as a “point with vectors.” Points have fixed positions, while vectors have magnitude and direction, but no fixed positions. In this overlap of voices, the stories of the granddaughter and grandmother share an origin point, surviving with and through each other. The moment feels both warm and reverent. The polyvocal elements of the poem lend to the image of a communion of spiritual ancestors, beyond just the grandmother. The grandmother, a higher power, uses her ability to create new theorems to connect with the granddaughter to pass on generational knowledge and joy, in ways that transcend physical, linguistic barriers.

While I was excited to see some of Vuong’s poems engaging with the works of the beloved Vietnamese musician Trịnh Công Sơn, the bilingual elements of the poems felt weak and secondary to simply alluding to Trịnh Công Sơn, to create the poetic atmosphere that lingered between wartime and postwar Vietnam. Rather than illuminating what Trinh’s songs mean to Vuong or how Vuong’s words reflect or refract Trinh’s grief and longing for Vietnam before the war, the poems distanced me from both artists.

When considering the poems individually, readers of Asian American poetry may find some tropes overused, some ideas trite. As a collection of poems, however, Vuong succeeds in exploring why the diaspora is pulled, reflexively or by necessity, to narrate what migration does and undoes to one’s relationship with family, mother tongue, and self. A Plucked Zither is a bold collection where Vuong presents an “anti-map” of herself and of the children of Vietnamese migrants. Vuong’s poems demonstrate how the shared experiences of the 1.5 and second generations of Vietnamese Americans continue to “make and remake” them—they are not so easily defined, whether by white America, their relatives, or in their personal turmoil to define their own relationship to Vietnam. But Vuong’s confident writing asserts that there will be some arrival, some destination in this identity work. “Say my name right, know my dead early,” Vuong’s narrator announces near the end of the collection. “Know my name as of others: Vương Thảo Phương.”

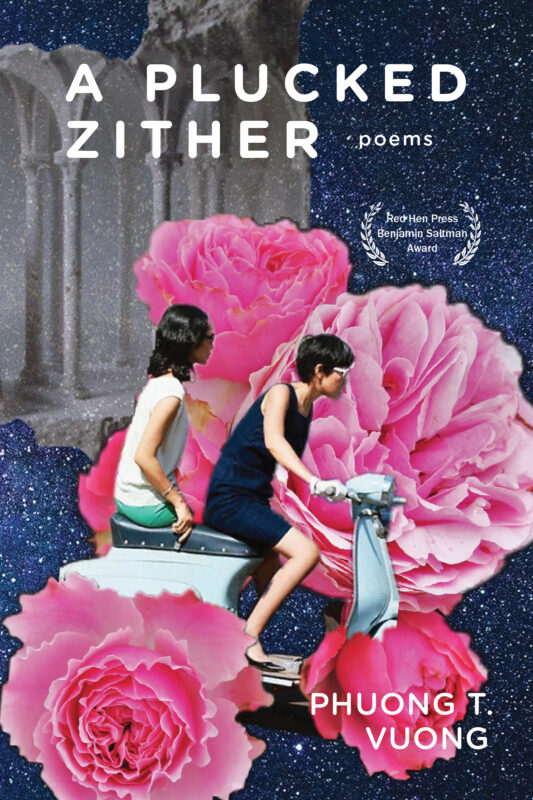

A Plucked Zither

by Phuong T. Vuong

Red Hen Press, $14.95

Cathy Duong is a current Masters student at UW Seattle Genetic Counseling program. In her free time, she enjoys traveling to Little Saigons, playing V-pop on her ukulele, and analyzing diasporic Viet literature.

Cathy Duong is a current Masters student at UW Seattle Genetic Counseling program. In her free time, she enjoys traveling to Little Saigons, playing V-pop on her ukulele, and analyzing diasporic Viet literature.