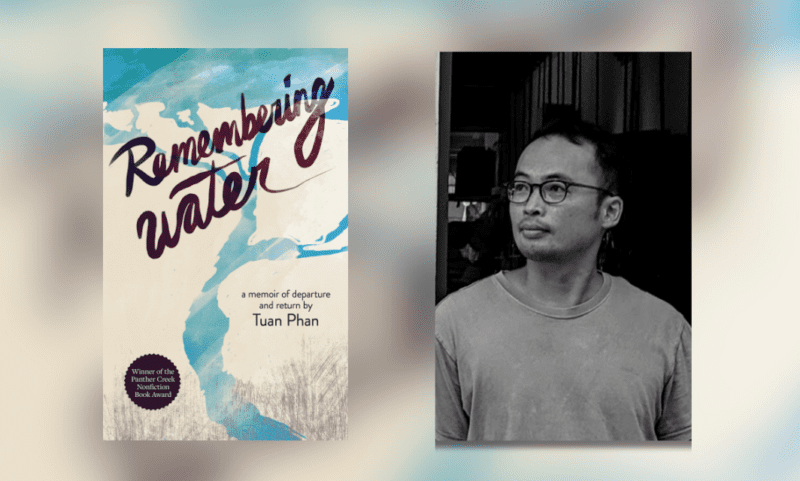

More than two decades after his family left Vietnam by boat, Tuấn Phan returns to a country much altered. His recent memoir, Remembering Water, braids childhood memories of Vietnam and his family’s departure with reflections on his current life in Saigon. Writer Cameron Walker talks with Tuấn about writing a path through the watery nature of memory.

Cameron Walker: I’d love to hear about how you got started as a writer.

Tuan Phan: I think writing and reading and engagement with language all go together. I learned English through reading first. First of all, I couldn’t speak without an accent when I first made it to the States. So I was very keen to assimilate and adapt to my new country. And the best way that I had to do that was to read as much as I could. And so I was a voracious reader—I was a voracious reader in Vietnam as a seven- and eight-year-old already.

I became very keen on learning to either tell stories or describe things by seeing how authors did it. I wrote in Remembering Water of my love for Mark Twain, for example. His descriptions of the river were so much embedded in my memories of the Mekong Delta and my adventures at my cousins’ on the Delta, and I translated the images that I remembered into what I was reading about the Mississippi River. That was how I was able to get engaged and get into the landscapes that I was reading about in America.

I wrote a lot in high school, just little bits and pieces and short stories and poems. And then I majored in literature—it was sort of a roundabout way to keep writing and keep thinking and keep reading throughout my university years. I actually was a playwright in university, I wrote plays and skits and was really engaged with theater there. Eight years ago, I took a year off from teaching and did a sabbatical in Vietnam to work on this full-length project. I started by writing little essays about coming back to Vietnam. And then they started compiling into something bigger and I thought, Oh, this could potentially be a book.

I had asked my old school for a year sabbatical, and then halfway through it, I just I told them, you know, thanks for this, I’m not coming back. I’ve been in Vietnam since then.

CW: Was it easier to write when you were in Vietnam, or did you do any of the writing when you were elsewhere? I know, for me, sometimes I have to be away from a place to think about it differently and be able to write about it. I don’t know if that’s the same for you.

TP: I think it’s a combination of both. The memories of Vietnam that I had of living here as a kid, that’s obviously written—or at least conceived in my head—while I was away. Even now a lot of those places aren’t here anymore, or they’ve changed so much, that I’m really writing at some remove. Even though I’m geographically here, that Vietnam and that Saigon is already in the past, so. So that remove helps me to write about it.

I do write about in the very last section how being here has taken away some of the vividness of those memories. When I was in America, I was thinking back to my childhood in Vietnam that I was yearning for so much and I think I recreated a vivid life around the details of the Saigon that I missed so much. So, I think you do write a little bit differently when you’re off-site, and also off-time from the location that you’re writing about.

In the first part of the book, I write about being here in 2007. My camera was stolen from my hotel room, and so in the mornings, I would just write down as much as I could, in as much detail as I could, what happened on the previous day. It was a long running list of what happened, a journal or a diary. From that, I was able to craft that into more of a narrative when I started to write this book again.

CW: When you were putting the manuscript together, how did you work out that structure? It always seems so hard to know what events to focus on and what to expand.

TP: When I won the manuscript competition with Hidden River Arts, it was a very different manuscript. I won the award in 2018, and in between the time I submitted it and heard that I’d won, I was still editing and revising it. So that initial manuscript didn’t actually have much of our first departure from Vietnam and our year in the refugee camps. It just had one short chapter that sped through that whole year. That version of the manuscript was more about the return and about embedding some of the memories into the return pieces—it was a collection of essays rather than a narrative memoir.

Then in the revision process, I realized that I wanted to write about the year of us being refugees, including the 10 days on the boat, with more detail. I was doing this after my sabbatical year, when I was teaching again, so I spent whatever time I could working on that section that eventually became the first third of the book.

I wrote to Hidden River’s editor and said that I was still working on the manuscript, and that I wanted to include this section, because I feel like it’s important and that I wanted to juxtapose the departure with the return. I felt like the way that we departed, and all of the turmoil that went into that, had an effect in in how we returned to Vietnam.

So the structure is something that I really, really had to work on for this memoir. And I feel like it still isn’t exactly right, but it’s right to the degree where I feel it could be read and enjoyed and understood. I really worked to connect that first third thematically with this last two thirds, which focus on the return intermixed with memories of Vietnam. I also wanted to juxtapose my father’s story with my uncle’s story, because I felt like they had very different characteristics and very different relationships to Vietnam.

CW: That’s amazing that the early chapters about the departure weren’t in the initial draft, because it is so powerful, and it’s such a balance of the turmoil—and then, for example, you’re looking at the stars and they’re beautiful, or experiencing the ocean on the island.

TP: Oh, thanks. It was a cathartic experience remembering that and writing it out, and there were tearful moments of writing, and then talking to my mother and interviewing her as well. I feel now that the book just couldn’t be the book without that section.

CW: I was reading an interview with Kimberly Nguyễn, who talks about water and how it’s such an important part of the language and the culture of Vietnam. I didn’t know how that became a part of the book, if the connection to water came as you were writing initially or emerged later.

TP: It’s so embedded in Vietnamese culture and consciousness, or maybe even the subconscious, that I didn’t intentionally lay out stories about water or stories that included water. But in the writing of it, and then in the revision process, I started to think about organizing it around water, and then thinking about the title as well. I came to the title fairly late. “Remembering Water”—if you use the literal Vietnamese translation word-by-word–is nhớ nước. That has all kinds of implications because those two words also mean missing your country—nước means water, but also country or nation, nhớ means to remember but also to miss, to yearn for. So those those two words together have layers of complexity.

At no point did I ever think, Oh, let me just insert more water imagery. It was already there, and in my way of remembering it, images of water grew more vivid and more important. At first, only the beginning of the book focused on my first memory of my father diving into the river near Biên Hòa, when, as a toddler, I tried to imitate him and fell, but ultimately, I decided to split the memory—to end the book returning to that memory, and then tying it to the memory of watching my father dive into the open ocean during our journey by boat, and, this time, how I followed him into the sea. At the end of the book, I think it captures that sense of displacement we felt, and this really strong sense of uncertainty that I felt as a kid after swimming in the ocean in the middle of our escape.

CW: Since the book has come out, I’m both wondering what’s next for you, and also whether your experience of Vietnam and of water have changed.

TP: I’m writing a collection of short stories is that set primarily here, with maybe a couple of stories about the diaspora in America. So that’s what I’m working on at the moment. Otherwise, I’m raising my family here. My son–he just swam in the ocean for the first time. We just brought him to Nha Trang. He’s not going to remember it, he’s just five months old—but I will.

Cameron Walker is a writer based in California. She is the author of National Monuments of the U.S.A., a book for kids beautifully illustrated by Chris Turnham. Her essays and short stories have appeared in publications including the New York Times, Carve, and Terrain.org.

Cameron Walker is a writer based in California. She is the author of National Monuments of the U.S.A., a book for kids beautifully illustrated by Chris Turnham. Her essays and short stories have appeared in publications including the New York Times, Carve, and Terrain.org.

Tuan Phan is a Vietnamese American teacher of literature, living in Saigon. He was born in Vietnam and left in 1986 with his family as part of a second wave of refugees. He has since returned to reconnect with his birth country. His memoir, “Remembering Water”, won the inaugural Panther Creek Book Award in Nonfiction and is published by Hidden River Press. You can connect with him on his website tuanwrites.com

Tuan Phan is a Vietnamese American teacher of literature, living in Saigon. He was born in Vietnam and left in 1986 with his family as part of a second wave of refugees. He has since returned to reconnect with his birth country. His memoir, “Remembering Water”, won the inaugural Panther Creek Book Award in Nonfiction and is published by Hidden River Press. You can connect with him on his website tuanwrites.com