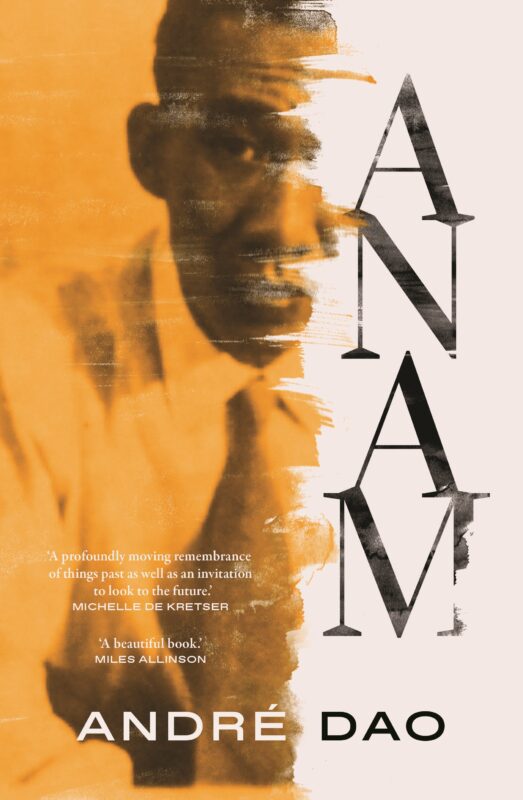

As an autofictional work that is part memoir, novel, and essay collection, Anam is a curious product of academic research, philosophical inquiry, oral history, and imagination, and the debut project of Vietnamese Australian writer André Dao. Dao weaves meditations on tenderness and love, phenomenology, and phúc đức between scenes of his grandparents’ life in Hanoi, Saigon, and France. In addition to being an artist and lawyer, Dao—and the narrator of his novel—is the cháu đích tôn of his family, the firstborn son of the eldest son. In Vietnamese tradition, it is the cháu đích tôn’s privilege and duty to carry on the patrilineal lineage by stewarding the family’s estate and maintaining the ancestral altar. But when one’s grandfather is imprisoned for ten years for being on the wrong side of the Vietnam War, and his family is displaced as immigrants in France and Australia, how does the cháu đích tôn fulfill his duties to his family and his ancestors? With no physical, ancestral homeland to inherit, Dao turns to theorizing about Anam, an abstract time-place that his family, as a diasporic people, reside in. The pacing of Anam is both driven and stalled by the narrator’s commitment to telling an accurate and ethical version of his grandparents’ story—a challenge that comes at the expense of committing to no version at all.

A continuous thread throughout Dao’s non-linear narrative is how institutions, whether academic, legal, or literary, shape the narrator’s understanding of self in relation to his family history and to society. From entering university to applying to jobs after graduating law school, the narrator believes that his acceptances into prestigious spaces had something to do with his refugee family story that institutions, committed to diversity and white saviorship, wanted to hear:

I was the son of refugees, the grandson of a political prisoner. There was an authoritative weight to that way of thinking and talking about myself that most of my classmates lacked. Especially the ones competing with me for internships and editorships, all of them as middle-class and well educated as me, but without that aura of authentic suffering.

Once inside the institution, one quickly learns that the value of the refugee, of people of color, is conditional, and complicity enables the ongoing repression of their voices. But no one else seems to insist on telling their family story as much as Dao needs to, and his partner Lauren thinks it’s “awfully conceited” to fixate on genealogy. Whether or not that’s a fair assessment, Dao internalizes his task as self-serving and egotistical. Setting out to officially write his family story, even if to fulfill his family duty as the cháu đích tôn, feels like another version of doing what got him into his current privileged place—establishing a self-mythos built on his family’s backstory of pain.

Dao’s narrator thus attempts to dissociate from any particular feeling about his family’s story—it was not his loss, so any emotional investment on his part would be like falsely laying claim to their pain. Professor Simons, his thesis advisor, observes this coldness in his drafts, and asks Dao what his grandmother’s predicament really means for him on a personal level—as in not intellectually, but what it feels like. Dao answers him:

Isn’t that the point though…Unlike Phan Boi Chau or my grandmother, I did not lose my country. I simply didn’t have one to begin with. How can you miss what you never had?…It’s not even that it’s vicarious. It’s confected. I have to work myself up to it. I have to do all this listening and reading and writing, to try to make this loss real for myself.

How Dao explains his loss recalls literary scholar Marianne Hirsch’s concept of postmemory. While Hirsch suggests that the creative processes of imaginative investment is an inevitable response to inheriting the past generation’s overwhelming, traumatic experiences, Dao sees his actions as a choice. He is “free to claim” and even “appropriate” his family’s loss of country. He harshly exerts judgment on himself for telling his family’s story in the way that he does—so sentimentally that it risks erasure of their suffering, and becomes palatable to a Western audience. He is experienced, after all, in favorably presenting himself and his clients as a human rights lawyer before those in power. And what Dao feels as a shameful confession, to admit that he is “someone who cannot feel his own loss,” Hirsch describes as a natural, albeit unfortunate consequence of inheriting postmemory, where our ancestors’ stories displace and evacuate our own life stories.

Professor Simons seems to follow Hirsch’s line of thinking. “Or,” Simons suggests to the narrator, “can you not feel your loss because it is so total? So total that your feelings are conditioned by that original loss—the primordial loss gives you your language and therefore sets the limit of your world?”

The extent of Dao’s meta discourse on writing his family story suggests that being a child of refugees in academic spaces produces a hyper-awareness about how powerful institutions view the “Other,” which disrupts Anam from otherwise being a straightforward family memoir. His level of concern with doing justice to his grandparents’ story even involves ethically considering whether to include the diacritical marks in Vietnamese names he discusses. “Fidelity to diacritics cannot recuperate or articulate all that history,” Dao admits, “If anything, it will only make it seem as if I know more than I do.” Interestingly, Dao’s overthinking never spills over into a neurotic tone or syntax. His prose remains effortlessly clear, calm, and engaging, even as he conveys a futility to do justice in his storytelling.

If anything, Dao’s meta discourse stalls the reader from enjoying Anam’s more poetic, literary elements—that is, when the narrator “I” and his endless reservations recede, having briefly committed to telling the readers a version of his grandparents’ epic story of love, phúc đức, and waiting. Tender scenes of his grandparents’ love story, from their first encounter, to the five years before their marriage, to their reunions, are held together by the symbolic veil of frangipanis. In one chapter, Dao immerses the reader in the September day in 1945 when Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s independence from France, and its significance for his Catholic grandfather who had been separated from his Communist brother Minh-now-Son. Dao structures the second half of the chapter as a series of questions, like an oral history interview, but the answers are brief and mystically poetic, as if accepting the role of fate in history:

Do the brothers’ paths converge?

No, never.

So was the pact between them broken?

It was.

Did the grandfather have names for what was thus lost?

He did.

Recite them.

Blood brother, bosom brother, first brother, playmate, idol, bully, friend, rival, lodestar.

Did the grandfather have names for what was thus gained?

Yes.

Recite them.

Brother-in-law, brother-in-Christ, mentor, master, Monsieur le Gouverneur, life’s purpose, morality’s measure, her brother, love’s brother.

In the second section of the novel, Aunt Phuong wonders how the narrator will write about the years that his grandmother and her children spent in the French town of Laon as refugees, waiting for news of his grandfather’s return. “Nothing happened” during this period, but “[Nephew] can’t redeem the waiting simply by showing that the event we were waiting for came to pass.” Dao rises to the challenge by writing what he calls “useful” fragments of the Great Anamite Novel, even if they cannot redeem the past. These fragments turn the section’s concluding chapter into a form similar to a play, where each relative gives a monologue that testifies to their waiting. Their words are dispirited by the Anam they lost, yet still hold power in their poetics.

In his review of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Committed, Dao writes that a novel is “a good technology for shaping the self.” Dao’s own novel succeeds in demonstrating this. The writing in Anam is no bold manifesto about inheritance, the effects of war, the refugee condition, or duty. Rather, Anam’s narrator is a writing companion, a guide by example, for the fellow child of the diaspora who is figuring out who they are, beginning with their family story. It was stunning to read my innermost concerns about writing about the past, so distilled in Dao’s prose. Dao’s concept of Anam is also a helpful thought experiment that does not tie the diaspora’s memoryscape of Vietnam to the present-day country of Vietnam. It recognizes that the country of Vietnam and its people have progressed in ways unrecognizable to South Vietnamese refugees, whose “Vietnam” is a nostalgic, unchanging Anam, of which different versions exist for each family, each generation. Dao’s depictions of his grandparents’ Anams are compelling across time and place, making Anam feel rich for adaptation as a play or as a historical novel. I’m incredibly excited to encounter more of Dao’s Anams through a multitude of genres in his future work.

Anam

by André Dao

Penguin Books Australia

Read an excerpt from Anam by André Dao.

Cathy Duong is a current Masters student at UW Seattle Genetic Counseling program. In her free time, she enjoys traveling to Little Saigons, playing V-pop on her ukulele, and analyzing diasporic Viet literature.

Cathy Duong is a current Masters student at UW Seattle Genetic Counseling program. In her free time, she enjoys traveling to Little Saigons, playing V-pop on her ukulele, and analyzing diasporic Viet literature.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!