George J. Veith’s Drawn Swords in a Distant Land situates South Vietnam at the center of the Vietnam War and the global Cold War conflict. In Veith’s opinion: “South Vietnam was always at the heart of the war.”

Departing from existing scholarship, Drawn Swords joins a growing trend to re-examine modern Vietnamese and Vietnamese-American history through the lens of the Republic of South Vietnam, delivering a perspective that is critical to counter revisionist history that casts South Vietnam as bystanders in our own history.

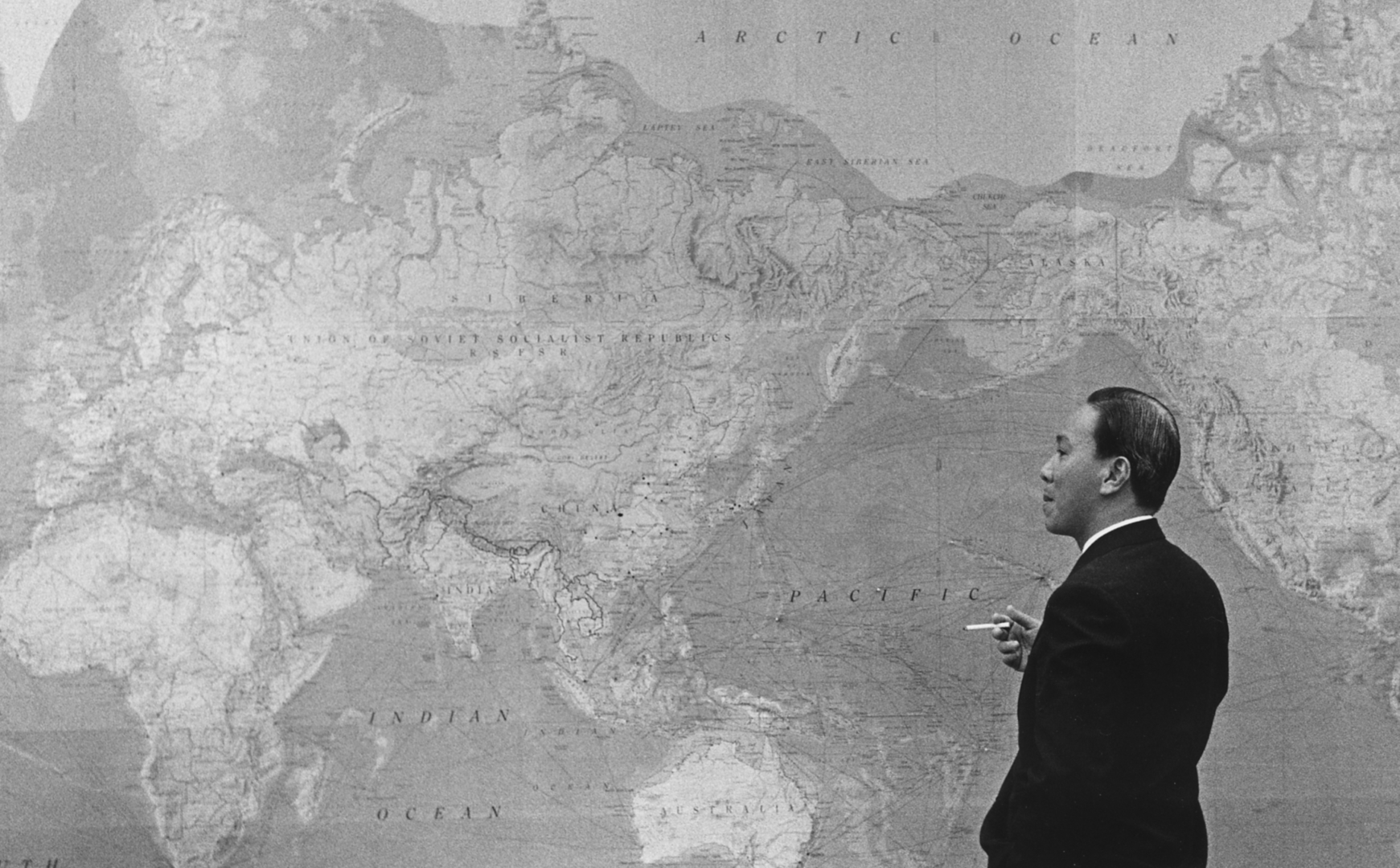

In Drawn Swords, Veith, who has already cemented himself as an expert on South Vietnamese military history with Black April: The Fall of South Vietnam, 1973-75 gives us an immersive look at the inner workings of South Vietnamese politics and the monumental efforts taken by the much caricatured South Vietnamese President, Nguyễn Văn Thiệu. When Thiệu, a 44-year-old Lieutenant General in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, took the helm in 1967, he was determined to build a democratic nation and to win the war.

In the words of Thiệu himself,

“Democracy cannot be built in a day. We need time to draft a constitution, to educate the people, to draft a referendum, and to prepare a general election for the national assembly to set up a civilian government.”

Each of these activities required an immense amount of maneuvering, haranguing, and corralling all spiced with the expected duties of a South Vietnamese President including hands-on work; negotiating political scandals, corruption, power plays, and rivalry; and handling day-to-day issues such as allegations of heroin smuggling.

Covering what Veith calls the “saga” of South Vietnam’s nation-building, Drawn Swords moves through “a four act play” from Vietnam’s 13th and final Emperor, Bảo Đại and his “State of Vietnam,” to Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm’s First Republic (1955–63), the subsequent chaotic four-year period following Diệm’s assassination, and finally to President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu’s Second Republic (1967-75).

Faced with a taciturn subject, Veith turned to his long network of trusted sources—South Vietnamese ARVN and those closest to Thiệu, including his wife, Madame Nguyễn Thị Mai Anh. Though we lost Thiệu in 2001, many of us in the diaspora remembered his legacy through his wife, Madame Thị Mai Anh, the First Lady of South Vietnam. Madame Thị Mai Anh, who recently passed away at the age of 91, was much loved for her kind and joyous disposition and the projects she shepherded for South Vietnam including her community hospital (Mrs. Thiệu’s hospital) and a school for the children of South Vietnamese soldiers.

Starting out with one of the most concise and well-organized write-ups about the tumultuous political forces within Vietnam, Veith details the highly factious, politically volatile world that Thiệu was born into. Set in the early 1920s, we are introduced to the spectrum of political parties, each with their own idea about the best strategy to deliver Vietnam out of French colonialism from Ho’s Việt Minh (Communism) to the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng (VNQDD – democratic socialism). Over time, Nationalist parties shifted from anti-colonialism to addressing anti-communism: “[f]or many Nationalists, fighting the Communist threat was more important than combating the French.”

In this primordial political soup, Nationalists were divided along political, religious, regional and ethnic-based lines. The pantheon of parties included competing and differing political philosophies (the Đại Việts and the VNQDD), the military (Khaki Party (Dang Ka Ki)), student-based groups, labor (Vietnamese Confederation of Labor), Communists (National Liberation Front), three political factions of Buddhists, the Catholics (Nhân Xã Hội), Cao Đài, Hòa Hảo, ethnic divisions (Khmer, Chinese, and Montagnards among many), and regional rivalries (Northerners (Bắc Kỳ ) and Southerners (Nam Kỳ)).

South Vietnam’s many factions created constant schisms in its fabric, which contributed to its weakness: “In reviewing the score card of political factions, religious schisms, regional hatred, and ethnic bigotry, many rightfully saw the Nationalists’ fragmentation, compared to the monolithic Communists, as South Vietnam’s greatest weakness, one that might well lead to its destruction.”

Most of Veith’s book fills out the flat outlines painted for Thiệu and thus, South Vietnam: “Western commentators usually painted Thieu in the same ideological hues that reflected their political outlook, and their heated rhetoric about him mirrored the absolutes of the era. Anti-war pundits typecast him as a corrupt, repressive dictator. The Communist Vietnamese simultaneously vilified him as a traitor and an American puppet. Internationally, his reputation was equally poor.” Veith begins his book with a brief overview of political drama under the First Republic under President Ngô Đình Diệm. Only by experiencing the events that led to Diệm’s execution/assassination are we able to then appreciate the work that Thiệu did in the Second Republic. Where Diệm’s leadership was authoritarian and nepotistic, Thiệu’s indicated a desire to modernize and decentralize South Vietnam to create an “ownership society” that advanced towards democracy.

Giving us insight into this trilingual South Vietnamese President’s vision, which Veith characterizes as “evolutionary and revolutionary, Veith argues: “Thieu wanted to create prosperity among the rural peasants by providing the South Vietnamese people a capitalistic environment that gave them a stake in their own development via self-rule.”

Taking us on a journey through Thiệu’s life, Veith offers gems such as a rare biography of the extremely private Thiệu. We catch a glimpse of his early beginnings which Veith gathered in his usual diligence from scouring past articles, media interviews, and interviewing those closest to Thiệu.

Drawn Swords delineates Thiệu’s vision and perseverance through incredible obstacles to attempt to build the nation he loved in the midst of a war. A brief account of Thiệu’s work, in addition to leading military efforts, included establishing a democracy, instituting land reform, wooing the peasantry in the countryside, decentralizing political rule, and ensuring more popular representation in politics. He did these while facing a score of challenges worthy of a serial drama including corruption scandals and allegations of drug smuggling.

Far from perfect, Thiệu also faced criticism for his dictatorial tendencies in cracking down on the press and those who supported his political rival, Prime Minister, Nguyễn Cao Kỳ. One of these, retold in great detail in Drawn Swords is the colorful events of the 1971 election beginning with the passage of a restrictive elections bill followed by back door lobbying (a.k.a. bribing and/or threatening) by Thiệu’s legislative advisor, Nguyễn Văn Ngan, to eliminate other presidential candidates. These events alienated the international community who drew their purse strings tighter and moved their favor away from South Vietnam.

Veith also spells out one of Thiệu’s greatest visions—his desire to launch an unprecedented land-reform campaign to create an ownership society and raise the living standard of South Vietnam’s peasants. His revolutionary land reform bill, the Land to the Tiller (LTTT) legislation, was his signatory tool “to wean his people from foreign assistance by working to build a new society based on self-reliance.”

Passed in March of 1970, the LTTT was the second part of Thiệu’s two phase program to “transform the lives of impoverished peasants” and to sway the allegiance of the peasantry towards Thiệu’s republic. The first phase involved restoring village authority and security. The second phase, with the LTTT as the first vehicle, was designed as a sharp contrast to the Communist model of collectivism and the poor track record they had for their bloody Land Reform Campaign. The campaign resulted in the massacre of over 172,000 “landowners” and “wealthy farmers.” Without “one single person being killed or publicly humiliated,” the LTTT, designed by the minister of agriculture and land reform, Cao Văn Thân, sought to go to the root cause of countryside poverty by redistributing all agricultural land in South Vietnam to farmers who were actually tilling the land. This included allowing farmers to keep land given to them by the Communist in the prior land reform program by providing them with a title to their plot. For plots owned by landowners, the LTTT compensated them—20% cash and 80% government bonds at a rate of 10% interest, guaranteed by the U.S., with a maturity rate of 8 years.