In the Diaspora: January 2024

►Half of Japanese firms in Vietnam seek expansion

►A large percentage of European plastic sent to Vietnam ends up in nature, finds study

►Tết celebrations held for Vietnamese in France, Germany

►Vietnam sentences ethnic minority man to 4½ years for religious activities

►Vietnam to Hold Arms Fair in December as Its Seeks to Diversify Supplies

►Chipmakers among 15 US firms eyeing $8 billion Vietnam investment: US official

►Vietnam attracts over 2.36 billion USD in FDI in first month of 2024

►Vietnam consistently refines its institutional framework to attract FDI

►Vietnam’s aviation sector to serve a whopping 842 million passengers in 2024

►Vietnamese make up largest percentage of Japan’s foreign workforce

►For better or for worse? South Korean men seek brides in Vietnam

►The Vietnamese: Inside Macao’s second biggest foreign community

►The woman who inspires love for mother tongue among young Vietnamese in US

►Vietnam needs a new leader

Reflections on the Oceans Before It Tries To Swallow Me Whole

1

i am unable to hear the sea’s whispers over the tourists’ voices.

i shut my eyes at the repeated flashes of their cameras.

2

the speedboat bloats over rocky waves and

i draw my fingertips over the ocean surface, revel

in the way the water pulls against skin

3

manong drops a rusting anchor somewhere into the sea and

i imagine the thud it makes, crashing into families of fry,

generations swallowed by rough membranes of sand

4

i think back to the iridescence of the reefs under this part of the sea

want to harvest the shattered bones of coral

5

manong helps me off the boat, cautions to watch

my step, so i don’t slip into the folds of the ocean

6

i want to tell him that in another life, that once, i used to call this home.

Julia Ongking currently lives in her beautiful home country: the Philippines. Born and raised as a Chinese-Filipino, she enjoys developing her perspectives through reading, writing, and having meaningful conversations with people from all walks of life. Her work has appeared in SAND Literature and Rappler Magazine, amongst other digital and print publications.

Julia Ongking currently lives in her beautiful home country: the Philippines. Born and raised as a Chinese-Filipino, she enjoys developing her perspectives through reading, writing, and having meaningful conversations with people from all walks of life. Her work has appeared in SAND Literature and Rappler Magazine, amongst other digital and print publications.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!

DVAN 2023 Writers’ Retreat in Southern France

On Friday, September 15, 2023, DVAN and ICI Vietnam, a French group that hosts Vietnamese cultural events, put together an event that brought 10 diasporic Vietnamese authors together into 3 panels of conversation in Paris, France. The event was the culmination of DVAN’s recent two-week long writing residency in Cazilhac, France. Held at the Jean Pierre Melville Mediatheque in the 13th arrondissement of Paris, a mostly Vietnamese and Asian neighborhood, the sold out event brought together bookish people of diverse age and race, making for an attentive audience. Three languages loaded with a shared history of colonization and war– English, French, and Vietnamese– are tossed through the air freely. Seatmates mix and match words as they make small talk; the library shelves rise above seated heads as the chatter winds down and the evening begins.

According to Isabelle Pelaud, the executive director of DVAN, this was the group’s first international residency.

The cohort consisted of four American Vietnamese authors, four French Vietnamese authors, one Vietnamese author and one Israeli Vietnamese author: Thi Bui, Bao Phi, Paul Tran, Vu Tran, Doan Bui, Anna Moï, Hoai Huong Aubert-Nguyen, Thuân, Nguyen Qui Duc and Vaan Nguyen. With the barrier of language, they mostly spoke English and broken Vietnamese among each other in Cazilhac, Vu Tran told me at a dinner held after the event. Even so, they engaged in productive conversations and made great connections, according to Hoai Huong Aubert-Nguyen.

“I really joined this residency to meet other authors from different cultural environments. …We talked, we listened, we engaged in dialogues,” Aubert-Nguyen said. “It helped me better understand their narrative styles, their esthetics, their oeuvres. Because we talked a lot about literature, but also art, music, graphic novels, traveling and cuisine. So it was very full and very diverse.”

The event was created in part to share those full and diverse conversations with the public. It was set up with three panels covering three distinct topics: “History & Memory,” “Gender in the Diaspora,” and “Literature as Activism.” Nguyen Qui Duc was unable to attend, but audience members enjoyed the additional presence of Line Papin, a 27-year-old award-winning French Vietnamese author who recently released an English translation of her book Les os des filles with DVAN. Along with two talented translators, LyLan Dill and Susan Dixon, and three mediators, Isabelle Pelaud, Jess Boyd and My-Linh Dang, the 15-person group offered insights into their work and, for the American authors, introduced themselves to a new audience.

“This type of gathering is rare in France.” said Gabriella, a younger attendee. “I became interested very quickly in what they were talking about. They covered themes I didn’t know about and I felt that suddenly I had all these new things to read.”

Pelaud agrees. It is uncommon to see discussions around diaspora in France. “One thing I realized since being here is how unusual it is for people from one ethnic group, especially people of color, to present together in a panel-discussion like this,” she said. “To feel a sense of belonging is a very powerful thing that maybe French (people) who are not people of color just take it for granted.”

The sense of diaspora, it seems, may be stronger among Vietnamese Americans, who live in a country with much larger immigrant populations. Translation into English is an enticing opportunity for some of the French authors associated with DVAN. Papin, speaking about her recent translation of Les os des filles with DVAN, noted that reproducing her work in English has made her feel more included in the Vietnamese diasporic identity.

“I think that the notion of community is very strong,” Papin said. “That’s why with the book I translated in the States, I was able to meet with all the authors in that community. In France the community feeling is less strong than in the United States where it’s very present.”

Along with bridging language barriers, onlookers of all ages were present. Each generation brought its own set of history and memories that seemed to build off one another in their questions and responses. During the “History and Memory” panel, author Vu Tran said, “We spent two weeks complaining about parents” and a wave of laughter came from the audience before his response was even translated. He continued, “I love them very much but I often feel like they created as many problems as they tried to solve.”

Speaking openly about these difficult relationships was a way for the authors to reveal the inspirations and histories that inform their creative work. For poet Paul Tran, the question of parent-child relationship went beyond history, feeding into their understanding of language as a tool more broadly.

“I grew up being the family translator and had to translate for my mom at the doctor’s office, at the grocery store, in line for food stamps. So I learned very early that words arranged in the right order, into the right sentence, into the right argument can recover her human dignity from people who felt like she had little intelligence, little heart and little to say,” Tran said. “I understood that (the) English language was how the United States fought its second war in Vietnam. So as a writer working in English, I have to fight…two wars. The one that my mother escaped, the one that the country waged on us after, and the one that continues to be waged on us everyday.”

When a community is spread among continents as the Vietnamese community has been, intergenerational dialogue is extremely dependent on the individuals’ journeys and experiences. By having an open discussion about these differences, a sense of community was felt among the differences.

“Our communities are being scattered and fragmented because of colonization and wars. For us it makes sense to work together, to exchange ideas, to discuss,” Pelaud said. “It’s not often done, these diasporic gatherings…a lot of our families have been divided, scattered, fragmented. That’s part of our history so it makes sense for us to gather. And the more we do it, the more I see the value of it. Everyone has been full of joy here (Cazilhac) for two weeks.”

For the authors, these types of conversations are fruitful not only for their work, but for their personal histories as well.

“I want to continue learning and hearing from others.” Nguyen said. “I think it’s very nourishing to listen and engage in dialogue with others.”

Conversations among space and time that promote this kind of connection were made possible thanks to the DVAN residency, according to Isabelle. The event’s goal was to share this knowledge with a larger community, and promote that connection outside of the world of published authorship.

“It’s almost as a gift. Here we are in this place for two weeks, it’s wonderful and we want to give back to the community by showing up and sharing,” Pelaud said. “The presence is an offering to the community.”

Note: We would like to remember Nguyen Qui Duc, who was originally meant to be part of the residency and the panel.

Melina Kritikopoulos is a mixed-race writer and journalist of Greek and Vietnamese descent. She is an undergraduate student at the University of California, Berkeley where she works for The Daily Californian. She produces and hosts the podcast Poetic Pontification, highlighting poets of the East Bay Area.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!

Melina Kritikopoulos is a mixed-race writer and journalist of Greek and Vietnamese descent. She is an undergraduate student at the University of California, Berkeley where she works for The Daily Californian. She produces and hosts the podcast Poetic Pontification, highlighting poets of the East Bay Area.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!

A Sky on Fire

Project Destiny by French writer Sophie Hieu is a hybrid memoir of hope, healing, and empowerment in the hands of nature.

At 30, most people are expected to have everything figured out: a job, an apartment, and a relationship. Yet for Sophie, something is missing: happiness, or even, destiny. With her ancestors wiped out by the Cambodian genocide, Hieu is haunted by the past. And she is determined to find her own answers. Trading her city life for a call of the wild, Sophie sets on an unexpected journey in the outdoors. But the more she ventures, the more challenges she faces.

The memoir was featured at the ICI Vietnam Festival in Paris. Though written in English, Project Destiny received a warm welcome from the French audience.

Below is an excerpt from Project Destiny.

~

The name meant in Sami “the lake of plenty.” With a thousand inhabitants, it had a thousand lakes. And the waters were abundant. They made the town swell. Not with fish as it used to be, but with cars. For in winter, the lakes froze. The cold blew on the landscape, turning the lakes into highways. And tires screeched and motors roared, as car testers came worldwide to test the latest prototypes and innovations. And the town tripled its volume. But deep in the bones, the town was empty.

The true North was a land of nothing. Of nothing to do. Nowhere to go. And no one to meet. For people were too few and distances were too long. The weather was too harsh. Under a spell, the North bled internally as people either died or fled. The shoal of fish kept heading south. And going North, hence, was swimming against the stream.

I never checked the map.

I just focused on people.

And that’s how they picked me. Against the stream. The North men.

***

“Is it your first winter here?” they asked.

The words faded as steam vanished in the air. The North men spared their breath and saved their words. Unless for something important.

I nodded optimistically.

“Well…”

They tilted their head, before looking at me seriously.

“If you make it here, you will make it anywhere.”

It was a small town. A desert. Where the sand is white, and the sky is black. Where mountains stand and rivers cry. Because the sun never rises. And the night always sets.

It became a refrain. For the North men all said the same thing. They played the same note. At first, I thought they were talking about the weather. It was common knowledge that the North was dark. And my lids, burdened by fatigue, slowly flapped until they closed. Like velvet curtains brushing the floor, I surrendered to eternal winter. Where blind men see with their eyes. And wise men look with their hearts.

Because eyes only see the obvious.

In the obvious, I was a fool.

***

“How can someone with such a training from Paris end up here?” they wondered. “The refugees,” I simply said.

They were my reason. In the daytime, I worked with them at the carpentry. We fixed benches, tables, and barbecues. In the evenings, I helped minors finish their homework. But it was never enough for me. Born an Asian, always an Asian. I had been raised with the idea that independence was work and money. And here I was, dedicated to a good cause, but without money. I was breaking my ethics. And losing my identity. I could not stop working. And I hated having no income. So, in addition to my voluntary work, I applied for two extra jobs. And got both.

In Paris, I had one job. In Lapland, I had four jobs. I juggled with them.

From 7 to 11 am, I catered breakfast at the family hotel nearby until lunch. From 12 to 4 pm, I would be of service at the carpentry.

From 6 to 9 pm, I would help the refugee boys.

On weekends, I would take shifts at the disco from 10 to 3 am.

I worked more than 70 hours a week. To earn less than a quarter of my pay. The year off was never a year off. I had never worked so much in my life.

***

“I don’t know how you can do this!” she exclaimed, positively impressed.

I smiled and grabbed the empty beer bottles. At midnight at the disco, the music was beating in my ears. All I saw were drunk people dirtying the place at incredible speed. Sonja was the manager of the hotel. Basically, she was one of my (numerous) bosses. And she hired me so to cater breakfast. The hotel mostly populated by car testers, having a slight feminine presence made the clients smile. This I realized as I stalked their plates and patiently waited for them to leave.

“You work so much! You are so strong! It is crazy how you manage all that! I would never!” she kept on enthusiastically.

It’s easy.

Just work.

Don’t think.

Don’t look at yourself.

Work is the most legitimate and common excuse not to think or not to fix problems. It is an illusionary ship that keeps the worker afloat, while it is still drifting from the land. Until it sinks. For work keeps you busy. It gives you money. But It cannot make you happy. She thought she was complimenting me. But she only reminded me of how hard I worked. For nothing. Nothing but the wind.

***

The months passed. In three months, three deaths. According to the locals, it was the “season”. Leaves detached from the trees. Flakes fell from the sky. And frost kissed the grass. They all aimed for the ground. Winter lulled men to endless sleep. As those next to us by evening would not make it by morning. While the living knelt, arms free, crying for the departed. And fearing for their own turn. And as they lit candles for memories, I stared at the windows. The night was set.

***

I was a loner. I became lonely.

I had offers to hang out. I had people to visit. The Europeans to ski with. The refugee boys to support. The Thai women to eat with. But all the time, I politely deferred.

I just stayed on my own.

Maybe because it was the North. Maybe because it was the land of the original people. But here, something was different. For the gold of Lapland was silence. A pure silence. Where time stopped and nothing moved. Until silence, to the attentive ears, made a sound. And everything became alive. The leaves whistled as the trees stretched to the clouds. The wind smooth-talked the breeze, sketching scales of a silver fish on the lakes. Sometimes, the ice broke, and a voice echoed from the depths. Under thick skin, something lived. I was surrounded.

***

At minus 20, I put a pair of joggings without extra layers. I run. I run around the lakes. Without stop. Without looking back. I just eat the miles. I don’t feel the cold. For I can’t stop. I can’t stop the pain. I can’t slow the rage. So, I keep running. I run to breathe. Vapor whirls. A cage swells. The bars contract. But they never break. The cold sows sharp daggers on the fields. A veil lifts with misty powder. Always forth, endlessly down. It traps the trees and ties the reeds. Senses acute, the wolf sleeps. Under a blanket of white fur, there is no room for darkness. And snow is cotton on a wound.

***

“You keep working because you don’t know what else to do.”

Laurent was a mountaineering guide. With a bear appearance and a ferocious jaw, he earned a reputation in town for being annoyingly brilliant and brutally honest. Laurent was a genius, not because he believed so, but because he was recognized so. A sharp mind with a foul mouth, I never refused to hike with him as it ended in philosophical debates. Besides, as a real French, he cared and retailed me with homemade jams, pastries, and cheese every week.

“Four jobs. And then what? Is it what you call a year off?” he snarled.

Only smoke was not coming out from his nostrils, but I could feel it.

“You work because you are a working machine. That’s what your parents did. And that’s what they passed on to you. But that’s not what you are supposed to do. You are supposed to do what you want.”

The more I worked, the more they asked me to work. For most of the people bailed. But not me.

“Call me when you stop.”

Laurent was right.

I had never been interested in drinking. I did not care about drugs. And I did not enjoy parties either.

But I was clearly an addict. I was addicted to work. I lived by duty. And I did what was expected of me.

An Asian worker. Someone who shuts up and works. Until exhaustion. Until death. I was unable to do what I wanted to do. And very far from being who I wanted to be. I had to stop.

So, for the first time in my life, I said no to work. And I called.

***

I cut the sound,

I sever the ties,

I drop the shield.

To walk in the dark,

I have no maps nor compass,

I don’t know where I am going,

I have no clue where I am heading,

But I keep walking,

Because that’s what warriors do.

That’s what my ancestors did.

They took steps before me.

They walked the path ahead of me.

To show me,

The way,

They walked the night.

They kept the light,

Even when they were shot,

Even when they were hungry,

Even when they were dying.

For I am them,

And they are me.

I am,

The war they fought,

The defeat they faced,

The blow they suffered.

I carry,

The rage they gave,

Their hope for peace,

The breath they passed.

In the fields of mines among trees,

Where humans bloom as flowers,

Parents become soldiers,

And children are war casualties,

Who sleep on the ground,

Or rise in the air,

To burst as shrapnel,

Blind bullets in the sky,

Who fire without eyes.

And here they stand,

Everywhere with me,

Nowhere without me,

Always within me,

As they tell me,

Keep walking.

They have not died in vain,

And I will not live in pain.

So, I take,

The steps they took before me,

And I walk,

The path they walked ahead for me,

The way of the survivors,

To finish their work.

I come closer,

Look closer,

And touch my own,

A shattered glass.

A reflection.

Of broken pieces of metal.

Darkness is a mirror,

It demanded no sacrifice,

Only an offering,

Acceptance.

For peace.

***

Generational Trauma

After Ocean Vuong’s “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong”

You’re never alone when you look in the mirror.

Your dad will always be your dad until one

of you forgets. Your mom will always be

your mom until you see her sun spots

as your own, her wrinkles become your defining features

and a silver ghost creeps from behind the back of your head

through a tangled knot in your thinning hair

until memories overlap,

Bố’s, Mẹ’s, yours –

______responding in a foreign language in your hometown

__________________________the soft ripples of the moon’s coldness

____________the cackling of white onions in spaghetti

________________laundry in cold showers

swimming lessons to make shore

__________bike rides for sugarcane juice

lying on the carpet watching the Sound of Music in theaters

__________________the stereo playing Beatle records

______a shipyard of cardboard boxes

Police sirens or city alarms trigger sweat behind your knees. You scratch

until you break skin. Blood on your hands, you can’t tell if they’re

______the same hands that buried themselves in the hole in your chest,

______the hands that wiped hanging tears from dry eyes,

______hands suppressing screams escaping a shaking body,

______or hands to hold you while you sit still in the space between return and the next line.

Thi Nguyen is an emerging poet, California native, born from Vietnamese refugees in San Jose, and is currently living in Los Angeles. Thi is in her final year at University of New Orleans, pursuing an online MFA in creative writing, focusing on poetry. She loves coffee and takes it with a splash of oat milk. Her recent interview with Marilyn Chin, regarding her latest book, Sage, can be read on Poetry Society of America.

Thi Nguyen is an emerging poet, California native, born from Vietnamese refugees in San Jose, and is currently living in Los Angeles. Thi is in her final year at University of New Orleans, pursuing an online MFA in creative writing, focusing on poetry. She loves coffee and takes it with a splash of oat milk. Her recent interview with Marilyn Chin, regarding her latest book, Sage, can be read on Poetry Society of America.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!

Remembering Nguyễn Quí Đức

“All immigrants and refugees, whether for a short moment or for the rest of our lives, will be obsessed and possessed by their past. It defines and perhaps nurtures us, giving us our identity, even when we struggle to develop a new self in a new home, a new land…” – Nguyễn Quí Đức

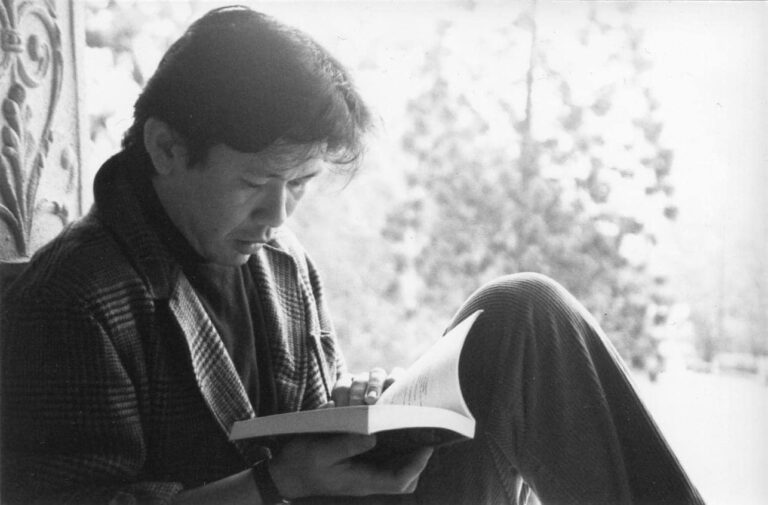

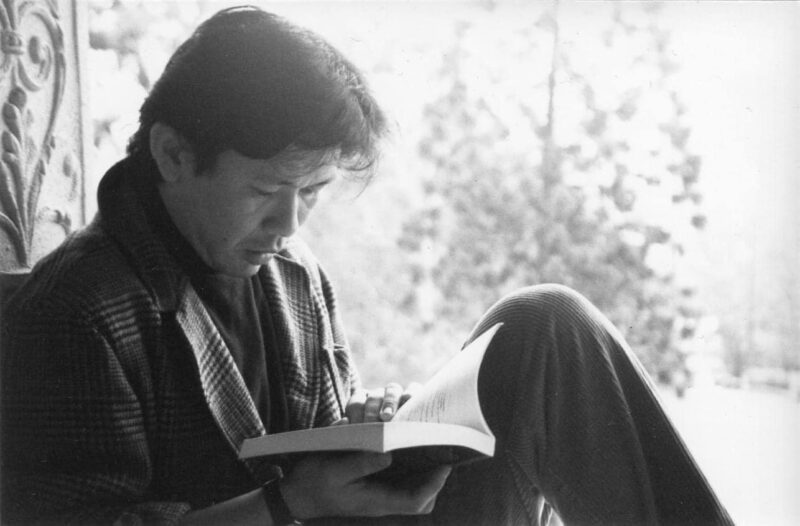

On the day of his passing, DVAN co-founder Viet Thanh Nguyen wrote on social media:

“This is how I remember Nguyễn Quí Đức. When I met him, I was in my early twenties and he was about this age in the picture [above]. I thought he was an old man. He was actually in his mid-thirties…. He was an NPR journalist when I met him and he gave me my first media opportunity, recording small pieces on the radio for his Pacific Rim show. He and I and several others started Ink & Blood, one of the first Vietnamese American arts organizations (it eventually became the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network). He wrote one of the first Vietnamese American books in English, Where the Ashes Are, a memoir. His father was the governor of Huế, and he became a world traveler and bon vivant. He eventually returned to Việt Nam and opened Tadioto, a bar in Hà Nội that was a meeting place for artists, exiles, diplomats, and cultural workers of all types to congregate. He bought a place in the mountains of Tam Đảo and turned it into an architectural showcase. He invited me to stay there by myself for a few days. He was generous with that house and everything he had, including his time. I think of his life as his most important work of art. That work is now finished. No one who knew him will ever forget him.”

Very few know that it is indeed Nguyễn Quí Đức who inspired Viet and I to co-found DVAN some 15 years ago.

Last September, we expected him to be at our Writers Residency in the South of France. He canceled the month before when he learned that he had an advanced stage of lung cancer. Along with so many others, we all mourn Đức.

Đức was our mentor, our friend, the person who always showed up and welcomed us. Last spring, when he visited San Francisco, he put forth the idea of creating a DVAN chapter in Vietnam, with Tadioto, his bar in Hanoi, as headquarter.

On a social media post, Monique Truong cited a quote from his essay “Memory”:

“The language of exiles is spoken

In the past tense – quá khứ.

We became nomads, modern cities

are the desert we cross, not so much

for salvation, nor for subsistence:

We cross our endless deserts, looking

For ourselves.”

To which Monique replied: “That desert was an oasis in your company, my friend. Thank you for showing us Viet Am writers how it could be done.”

This sums it up. This desert oasis is what I wish for DVAN one day: to have and hold a space for writers, poets, storytellers, and musicians to gather around a drink and share their soul to those who would listen.

I wrote about Đức and his influence on us in the foreword of the 25th anniversary edition of Watermark: Vietnamese American Poetry and Prose:

“When Nguyễn Quí Đức’s book Where the Ashes Are came out in 1994, I readily joined a small group of Vietnamese American students who offered to help him, mostly by making a show of support at his readings. He welcomed us to his small apartment in the gritty Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, and after a couple of brainstorming sessions and reading groups, his place would always teem with people talking, smoking, drinking, and eating. It was there, while we were all piled up on his mattress on the floor chatting, with a large painting splattered with red paint floating overhead, that we conjured the extravagant idea of writing our own poems and stories and presenting them to the public ourselves. We wanted to see Vietnamese American poets and writers together on stage, sharing questions and ideas like the events we’d seen at our universities. It was fun to dream.

“At this time, Vietnamese American scholars and artists were not on the Asian American Studies radar because we were seen as too anti-communist and unconcerned with racism. According to Nguyễn Quí Đức: ‘Refugees from Vietnam were then seen as descendants of people in the government of South Vietnam, corrupt officials—and we didn’t fit in the stories of earlier Asian Americans who came from the civil rights movements (while the Vietnamese identify more as Cold War refugees). This accounts for the reluctance of the Asian American communities to accept and welcome the Vietnamese in the beginning until we were seen as a group that could add a voice and strength to the Asian American communities.’ In addition to not being readily included in Asian American activist circles, neither were we invited to established white spaces, because we had not experienced the war as adults, or for those who had, they were judged as failures responsible for the loss of the war. Our numbers were relatively small, and there were also not many established bodies of literary work to be proud of, stand on, or depart from. But when Watermark passed from hand to hand at the gatherings at Đức’s place, the terrain of possibility shifted….

“…We called ourselves Ink & Blood. In the core group was Nguyễn Quí Đức, of course, and also Thien Do, Mộng-Lan, Sonny Le, Thuy Linh, Van Ly, David Nguyen, Hai Dai Nguyen, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Thai-Anh Nguyen-Khoa, De Tran, Trung Tran, Erin Khue Ninh, Cindy Quynh Trang Nguyen, Michael Huynh, and Tu Vu. Nguyen Qui Duc reflects on this time: ‘For many among Ink & Blood membership, the group served as a way to break out of the demands of the community for us to be engineers, doctors, IT tech types…. Ink & Blood faced similar issues that Kearny Street Workshop in San Francisco or the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in New York faced. One was concerned more with promoting community voices from within, the other also interested in getting such voices published and out to a larger readership beyond the Asian American communities.’

“As Ink & Blood, we built a grassroots network of Vietnamese American writers and artists: Nguyễn Quí Đức would find a location (he had connections with the San Francisco Public Library, the Montalvo Arts Center, and the San Francisco Arts Commission) and graphic designer Thien Do would design a flyer, which the rest of us would distribute through email and announcement boards. At these events, we all arrived early to set up and left late after clean-up. In this decentralized process, we searched for poets and writers, such as Andrew Lam, to include in our programs. Since there were so few writers, we ourselves wrote poems or stories for the events. There were no official meeting minutes and no budget, yet large crowds would show up at all our readings. I still recall one event themed around ghost stories. We thought it would be easy, as all of us had grown up with them. We had found a local art center in the Tenderloin that could host. In a makeshift effort to set the mood, we turned off the pale overhead lighting and lit some small candles arranged in a large circle on the floor. The room was full of people, spilling out into the street. As we gathered around the candles to start the reading, however, we were dumbfounded to find out that none of us had prepared an actual ghost story, each of us counting on the other to do so. With this awkward realization, we read whatever we had or improvised. I read an account of a nightmare that I had the week before. Having been taught to never stand out, never speak out, and never tell, we found the process of reading in public both nerve-racking and exhilarating. The audience was supportive of our effort but also clearly disappointed. Looking back, our failed ghost stories night perhaps reflected our unsettled identities, ones that we as migrants were still struggling to figure out…. So we made it up as we went, writing in the dark, hoping that we could really center our own writing one day without fully believing that it would ever come.”

It is no coincidence that our first Southeast Asian imprint with Kaya Press is called Ink & Blood. This imprint in which we are translating diasporic Southeast Asian books into English is an homage to Đức. He will always remain in our heart, our mind and our soul.

Isabelle Thuy Pelaud is the Executive Director and co-founder of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network. She is the author of This Is All I Choose To Tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature and the co-editor of the award-winning Troubling Borders: An Anthology of Art and Literature by Southeast Asian Women in the Diaspora.

Isabelle Thuy Pelaud is the Executive Director and co-founder of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network. She is the author of This Is All I Choose To Tell: History and Hybridity in Vietnamese American Literature and the co-editor of the award-winning Troubling Borders: An Anthology of Art and Literature by Southeast Asian Women in the Diaspora.

Liked what you just read? Consider donating today to support Southeast Asian diasporic arts!